Southern Food Blog

Colonial Foodways

by Jean Worts

The meeting of the Powhatan tribe and the English settlers centuries ago at what is now known as Jamestown marked the birth of American culinary traditions. The first colonies established by the English, Spanish, and French began the intermingling of European traditions and food ways with those of the Native Americans all along the Atlantic coast in early settlements. Although the settlers brought with them various foods and animals, they soon found themselves interacting with New World foods. This interaction changed their diet and highlighted the stratification of wealth among the settlers. Aboard the ships of European settlers were “horses, cattle, goats, sheep and chickens, as well as pigs; they brought apples, turnips and cabbage; they brought wine, brandy, rum and malt brew”—the rest was provided by the New World (Egerton 11).

The first settlers to colonize America were primarily male, but when African slaves and women began arriving ashore, the colonies were quickly transformed into a permanent living community, rather than one used simply for trade, and the focus on the social aspect of living was intensified (Egerton 13). As Spanish settlers scoured the Caribbean setting up base camps for exploratory adventures, the first permanent settlement in the United States emerged in St. Augustine, Florida in 1565 where cooking techniques—barbacoa— and cooperative live stock raising with the Pueblo Indians shaped the nature of the Spanish settlements (“Spanish” 1). Perhaps the most important was the adaptation of barbacoa as a means to slowly smoke meats into what we now refer to as barbeque.

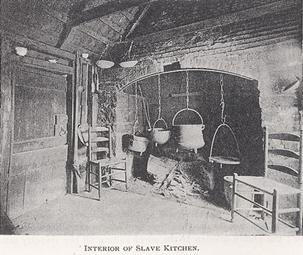

Throughout the colonies, foods were beginning to take on a distinct nature as influences from European settlers, African slaves, and Native Americans were seen throughout the kitchen. In the English colonies “most cooking was done in the open fire place in pots and kettles brought from Europe;” while the upper class used several of these for each meal, the poor lower class would have only one pot or kettle to cook a meal in, decreasing the quality and substance involved (Egerton 14). Without refrigeration to preserve foods, colonists had to rely on smoking or salting their meats and eating only the available fruits and vegetables in season. These foods were prepared using many of the same cooking techniques we use today, including frying, roasting, baking and boiling—and the content of what was consumed still lines our grocery shelves: beef, lamb, pork, chicken, fish, vegetables, and baked goods, with seasonings like sugar, cinnamon, and nutmeg used liberally (Crew 1). Lynn Olver, an International Association of Culinary Professionals member, explains, “The ingredients used by Salem cooks in the 1690’s would have been a combination of ‘New World’ foods (corn, clams, squash, beans, cranberries, potatoes), local fare (mollusks, fish, wild game, fowl/birds, domesticated hogs, apples, nuts, berries, onions, cheese, eggs) and imported goods (tea, coffee, sugar, rum, citrus fruits, spices, and flavorings)” (Olver 6). The most popularly consumed food was meat, and often several meat products were served within the same course of multicourse meals. All parts of the animal were consumed, and “they considered animal organs, like hearts and brains, tasty delicacies” (Crew 2).

As colonial dining evolved in the early stages of settlement, meals became more of a social event in direct proportion and as a reflection of wealth. Breakfast was taken early in the day for the poor before the day’s chores were to begin—for southern planters, it was served after the morning chores as a leisurely meal (Olver 3). Dinner was the social, large meal eaten at midday and supper was often a small evening snack of leftovers from the day’s previous meals if it was eaten at all (2). Alcoholic beverages were consumed with each meal, including breakfast which usually consisted of a cider or beer coupled with a bowl of porridge that was prepared the night before and cooked slowly through the night or a cornmeal mush with molasses (3). While breads were eaten throughout the day, they were most certainly served at breakfast.

As the biggest meal of the day, dinner was served as several courses. Lynn olver documents, “the first course included several meats plus meat puddings and/or meat pies containing fruits and spices, pancakes and fritters, and the ever present side dishes of sauces pickles and catsups… soups seem to have been served before or in conjunction with the first course (3). Other courses comprised of stews with vegetables and pork, and desserts of fruits, cakes, custards, and tarts; these assortments were plentiful in a two course dinner for the financially comfortable in the late 1700’s (3). The small meal of supper would typically consist of bland potatoes and an alcoholic beverage. For the southern planters, eggs would be consumed as “delicacies” as a special side dish with supper or dinner (3). Most Virginians fell into the lowest stratification of society and “prepared basic soups and grains porridges… supplemented with whatever meats and vegetables they could obtain” (“Food ways” 1).

Food, in America’s formative years, was a primary indication of social status and wealth. Those that could afford to would prepare elaborate, labor intensive meals to entertain guests and show off their affluence. John Egerton describes southern cuisine prior to the Revolution as “remembered in the history books and cookbooks primarily as the cuisine of the upper class” (Egerton 14). Women would direct the servant-cooked meals in the kitchen in higher society, but even in the middle class, there existed only a small portion of whites that did not have servants.(“Food ways” 1). Many of these traditions and food stuffs are still prevalent in American cuisine today highlighting the transcendence of European and Native American influences in the colonial era that have created what now exists today as our culinary tradition.

Works Cited

Crew, Ed. "The official site of Colonial Williamsburg - Colonial Food ways." Colonial Williamsburg Official Site. 17 Apr. 2009 <http://www.history.org/Foundation/Journal/Autumn04/food.cfm>.

Egerton, John. Southern food at home, on the road, in history. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina P, 1993.

Olver, Lynn. "The Food Timeline: history notes--Colonial America and 17th & 18th century France." Food Timeline: food history & historic recipes. 17 Apr. 2009 <http://www.foodtimeline.org/foodcolonial.html>.

"Spanish Colonization in the North." Travel and History. 23 Apr. 2009 <http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h438.html>.

Hog Killing

by Kaitlin Schlosser

Pork has been an important part of the Southerner’s diet since colonial times. The hog was a way for Southerners to not only provide for their own family but for others as well. The hog was an important source of food because the entire hog was useful in some form or another. “The animal [hog] did not offer its owner milk or the ability to carry burdens, but nearly all of the pig was edible or useful in some manner of cooking: hams, ribs, head (for souse), feet, internal organs (intestines for chitterlings), and lard or fatback (as grease or seasoning)” (Bass). This is a prime example of the utility of the entire swine.

Hog killing was a profitable business, and it has always been prominent in the South (Bass). They were open range animals, and they initially outnumbered people, hence their popularity in the food chain (Thompson). As hogs ranged freely across the land, eating an assortment of nuts found on the forest floor, farmers quickly learned that the taste of the creature was sacrificed. For instance, if a hog were to eat numerous chestnuts, their meat would have a sweet taste but would be essentially useless for white lard. Additionally, if a hog were to eat acorns, their taste was bitter and the consistency of their fat was altered. Therefore, farmers would bring the pigs that were going to be slaughtered down to the farm anywhere from a week to a month beforehand. They would be fed a steady diet of corn and this allowed for the familiar taste of pork that everyone knew and loved (Wigginton 189).

The slaughtering of a hog would typically take place in late November. This time was better because the weather was becoming colder and would stay that way. Because freezers were virtually unheard of, the cold weather was important to farmers in order to keep the meat while it cured. Everything was done at the home of the farmer, and the process was a grueling one (Wigginton 189).

On the day of butchering, scalding hot water was prepared for the hog. There were a few different ways of preparing this water. Some people had a cast-iron bowl that was approximately four feet in diameter that would be set into a stone furnace. The bowl would be filled with water first, then the farmer would build a fire in the furnace. The bowl would be placed inside, allowing ample time to heat the water as the hog was killed. Other people would have an oil drum that was tipped on its side and filled halfway with water. Heated rocks would be set within the water in order to warm it up. Lastly, others would simply heat water on their stoves and pour it over the carcass of the swine directly (Wigginton 190).

The killing of the hog was a quick process. It was typically killed by a swift blow to the head with either a rock or an axe head, or the swine was shot in the back of the head or between the eyes. As soon as this was done, the jugular vein was immediately cut open in order to help drain most of the blood from the body. When the bleeding had slowed, the swine’s carcass would be placed into the hot water then rolled over in order to loosen all of the hairs lining its body. In order to remove the hair, one would either pull it off or scrape it off with a utensil such as a knife. This process was continued until all of the hair was removed from the carcass. If the hog was left in the water for extended periods of time, the hair would set in the body and become harder to remove (Wigginton 192).

Once the hair was removed, the hog’s hamstrings were exposed and a singletree was placed behind the exposed muscles in order to tie the hog onto a pole that was placed securely in the forks of two other trees. This would leave the hog dangling with the stomach exposed. At this point, hot water was poured over places that had not yet been cleaned to remove all other debris. Once this was finished, the neck was cut at the base of the head and all the way through. After this incision was made, the farmer would twist the head of the swine off and set it somewhere else. The rest of the blood was now drained from the body (Wigginton 192 – 196).

Once the remaining blood finished draining, an additional cut was made down the underside of the pig. It went from the crotch all the way up to the throat. The farmer must be careful not to cut the membrane holding the intestines. Next, the farmer would follow the following procedures. “The large intestine was cut free at the anus, the end pulled out and tied shut, the gullet cut at the base of the throat, the membrane holding the intestines sliced, and the entrails allowed to fall out into a large tub placed under the carcass. The liver was then cut up and set aside to soak for later use. Also set aside and saved, in most cases, were the lungs, heart, and kidneys. The valves, veins, and arteries were trimmed off the heart, the stomach and small intestines retrieved from the entrails, and all were drained, washed, and set in water to soak while the cutting continued” (Wigginton 196).

As soon as this process was completed, the hog was untied and taken down in order to cut up the meat. Depending on the size of the group helping, people may be enlisted to do a number of things. For instance, one group of people may begin slaughtering a second hog, another may start to prepare the entrails and organs since these needed to be used promptly, and yet another group would cut up the carcass of the hog that had just been removed from the tree. Two pots would be prepared at this point. One was a “sausage pot” that would hold the trimmings of lean meat and the other was a “lard pot” that would hold the trimmings of fat (Wigginton 196).

The most common way of cutting up the carcass of the hog was to remove the fat that held all the intestines together, known as leaf lard, and throw it into the “lard pot” in order to turn into lard and cracklins later. As the swine was still hanging, an incision was made down the entirety of the back and into the backbone. The hog was then placed onto a hard surface where its body would be cut into slabs of meat. The tenderloin was the first section to go, followed by the two sections of rib cage. The rest of the pig remaining would be cut up accordingly. Traditionally, the backbones and ribs are usually canned. The tenderloin would be cooked at once, along with the heart, lungs, liver, kidneys, and head. The sausage would immediately be ground up (Wigginton 196 – 197).

One can easily note that pork has been a key ingredient in southerners’ diets, for the hog could easily feed multiple families. All parts of a hog were useful in some form or fashion. In a time where self sustainability was important, the swine was a profitable business that kept numerous families going. Pork continues to be a popular meat in the South today due to its long history, and it will continue to be so.

Works Cited

Bass, S. Jonathan. "'HOW 'BOUT A HAND FOR THE HOG': THE ENDURING NATURE OF THE SWINE AS A CULTURAL SYMBOL IN THE SOUTH." Southern Cultures 1.3 (1995): 301-320. America: History & Life. EBSCO. [Tarver Library], [Macon], [GA]. 20 Apr. 2009 <http://proxygsu-mer1.galileo.usg.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ahl&AN=A000426979.01&site=ehost-live>.

Thompson, Michael D. "'EVERYTHING BUT THE SQUEAL': PORK AS CULTURE IN EASTERN NORTH CAROLINA." North Carolina Historical Review 82.4 (2005): 464-498. America: History & Life. EBSCO. [Tarver Library], [Macon], [GA]. 20 Apr. 2009 <http://proxygsu-mer1.galileo.usg.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ahl&AN=A700002719.01&site=ehost-live>.

Wiggington, Eliot, ed. The Foxfire Book. New York: Anchor, 1972. 189 – 198.

Church Food

by

Allison Doerr

Both food and religion are very important in the South, so important that in her essay on Religion and Food, Corrie Norman claims, “church food is southern food in the South” (3). There are many different ways in which we can see food and religion coming together in the South. These can be seen in stories in the Bible, in the Church services, and in the activities of the congregation away form the services. From religious based rituals to community based rituals, “food is highly symbolic, and food rituals exist in most religions” (Norman 2). These rituals create a stronger since of community in the church congregation by bringing people together to both prepare and eat the food.

The first place where we can see food and religion coming together is in several Bible stories and teachings that center around meals and food practices. An example of one of these teachings is in the practices of Lent. In the true following of Lent, one is to fast during the entire season. In some cases this fasting is taken to mean not to eat during the daytime, while others will only eat one meal each day. Many people decide to instead fast from one particular food during Lent. However, Catholics and similar denominations refrain from eating meat on Fridays no matter what, even extending beyond the season of Lent ("Food culture and religion"). The most important Christian food ritual recreates Christ’s Last Supper. During this meal, Jesus ate bread and drank wine, and he told his disciples to continue to do “in remembrance” of him. This translates into the celebration of Communion. In the Catholic, Episcopalian, and Lutheran churches, the Eucharist is taken every week, and they also believe in the transubstantiation – the belief that the bread and wine are literally transformed into the body and blood of Jesus when they are consumed. Many southern Protestant churches observe Communion less frequently. This change is significant because is deemphasizes the importance of the religious food ritual.

The emphasis in Baptist and Methodist churches seems to be shifted instead to the food rituals of church dinners. In the South, the first thing that most people think of when they here the phrase “church food” are the Sunday afternoon suppers or Wednesday night family dinners at their own church. These meals tend to be potluck or covered dish affairs. Church dinners create a stronger sense of community in the Church congregation are somewhat reminiscent of the Last Supper. Norman explains that “the covered dish supper laid out for everyone to help themselves to food taken from the same pots and eaten at communal tables symbolically relates to the supper at which Christ and his disciples shared common dishes” (3). In this way, we can again see how emphasis has been shifted from the religious ritual, Eucharist, to the community ritual centering around food in the protestant churches.

There are a few different ways in which the stereotypical church dinner originated. One of these origins is the evangelical camp meetings of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. These meetings lasted from all day to all weekend. The members would eat picnics of food that they had prepared at their homes, and brought with them. Usually the meal would be prepared from ingredients that were grown or raised by the family or in the community. This would add to the sense of community in two ways depending on where the ingredients were from. If they were from a certain families’ own garden or farm, then they would be bringing their unique product to the table for everyone to enjoy. If they used ingredients from various members of the community, then the dish or meal would literally be a blend of different elements of the community. This blending would also bring the people together and strengthen the feeling of community. As time moved on, people continued to have picnics on the church grounds, however it became encouraged to bring enough to share, and then possible to cook meals at the church (Norman 1). These church potluck suppers create a strong sense of community, which can be seen in the homecoming and other large celebration meals where in “one mill village [the] church has only 60 members today; but over 300 ‘came home’ to its recent homecoming celebration” (Norman 5).

African-American churches also incorporate food and fellowship into church services. Psyche Williams-Forson explains in Building Houses out of Chicken Legs that, “ having spent most of the entire day in church, […] many congregants would not have the time to travel home and back to make it to the late evening service. Because most of the country churches were also devoid of any form of kitchen facilities, women would prepare the meals at home and, during a break in the service, would spread their meals on blankets and other coverings to serve” (136). The act of preparing these meals together and the signifying (back and forth banter) that goes on between the women preparing the food is a way of creating a stronger community among the women in the kitchen. The meals prepared by this smaller community “allowed worshipers to enjoy not only the fellowship of the spirit but also the fellowship of the members whom they would see only during these occasions” (136).

Food plays many and a wide variety of roles in church life. It is important in following and staying connected to one’s own religious faith by following teachings concerning food, such as Lent and Communion. However, it is also significant in personal lives. Church food allows people to develop a stronger since of community as a whole, and to find their place in that community.

Works Cited

"Food culture and religion." Better Health Channel. Jan. 2009. 22 Apr. 2009 <http://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/bhcv2/bhcarticles.nsf/pages/Food_culture_and_religion?OpenDocument>.

Norman, Corrie E. "Religion and Food." The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture 7 (Sept. 2007). Southern Foodways Alliance. Center for the Study of Southern Culture. 26 Mar. 2009 <http://www.southernfoodways.com/images/Encyclopedia%20Religion%20and%20Food.pdf>.

Williams-Forson, Psyche A. Building Houses Out of Chicken Legs. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

Farmers' Markets

by Carrie Coburn

Americans’ attitudes toward food have changed radically in the past fifty years. In Georgia, for example, we have transformed from a largely agrarian society to one where many children grow up unaware of how our food is produced. In recent years, we have seen a push back towards localism and organically grown produce. With the development of the local food movement in America, farmers markets have become increasingly popular because they provide many benefits to both the local community and small farmers. There are many different types of farmers markets in the U.S., all with different regulations about the products being sold and not all farmer markets require that food be locally produced or organically grown. Markets similar to those found in the United States can be seen in countries all over the world. Shopping at a local farmers market can be a beneficial solution for those of us who are not blessed with a green thumb or acres of farm land.

Agriculture remains Georgia’s largest industry, contributing 15 percent of the state’s employment and 12 percent of the value added in Georgia’s economy. There are currently about 50,000 active farms in the state, 65% of which are small farms that produce less than $10,000 per year in sales (Flatt). Yet, many small farmers still struggle to make a living. Restaurants and grocery stores no longer turn to locals for farm fresh products. The American consumer has no concept of “out of season” produce. Regardless of the time of year, nearly any fruit or vegetable is available in the local grocery store. Our globalizing world allows us to easily ship produce across the country and around the world: we have mangos from Jamaica, asparagus from Peru, oranges from California, and even apples from New Zealand. As these fruits and vegetables rack up frequent flyer miles, they also have a tremendous impact on the environment. According to Steven L. Hopp in Animal, Vegetable, Miracle, “Each food item in a typical U.S. meal has traveled an average of 1,500 miles…If every U.S. citizen ate just one meal a week (any meal) composed of locally and organically raised meats and produce, we would reduce our country’s oil consumption by over 1.1 million barrels of oil every week” (Kingsolver 5).

Farmers markets are not a new creation, but they have been booming in popularity all across the country. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the total number of farmers markets in the United States in 2008 was 4,685, double the number in 1998. The state of Georgia alone has well over 40. Farmers markets provide an outlet for farmers to sell their farm fresh products to the public. They can be state, city, or community operated, and each market has their own rules regarding who can sell and what can be sold. These markets benefit both the farmers and the local community by giving customers access to excellent fresh produce at an affordable price. At most farmers markets, the produce is locally grown, often organically, and picked when it is at the peak of the season, when they taste and look the best. An added bonus to buying directly from the farmer is that the prices are often significantly cheaper than grocery stores or supermarkets. Without the costs related to shipping and packaging, customers receive better quality food at a wholesale price. It is also extremely easy to locate a farmers market anywhere in the US through the U.S.D.A’s website or in Georgia through the Georgia Department of Agriculture.

In many countries around the world, open air markets are the norm. A weekly market day is a normal occurrence in cities and towns across the globe. France and other European countries are well known for their street markets. Paris has about 80, each selling its own assortment of unique wares, attracting all different types of customers. Some markets are known for their fish, cheese and bakeries, others for their organically grown food and ecologically correct products (Fayard). Prices vary from market to market based on the quality of the products being sold.

The number of increasing farmers markets in the U.S. indicates a change in the American mindset toward food. Many people have begun turning to local farmers to provide them with good quality, fresh produce. By doing so, we are strengthening our local communities and providing support to small farmers in Georgia and across the nation. I believe that taking advantage of farmers markets will provide many benefits for the future as well, hopefully encouraging more sustainable farming practices as well has reducing our impact on the environment.

Works Cited:

Fayard, Judy. "Open-Air Markets." France Today 22.5 (June 2007): 8-10. Academic Search Complete. EBSCO. Tarver Library, Macon, GA. 30 March. 2009 http://proxygsu-mer1.galileo.usg.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=25047116&site=ehost-live

Flatt, William. “Agriculture in Georgia: Overview”. New Georgia Encyclopedia. University of Georgia, 2004. < http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-2056&hl=y>.

“10 Principles of a Successful Farmers’ Market”. Farmers Market Federation of New York. http://www.nyfarmersmarket.com/pdf_files/marketprinciples.pdf

“Farmers Markets”. US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Marketing Service. http://www.ams.usda.gov/AMSv1.0/ams.fetchTemplateData.do?template=TemplateC&navID=FarmersMarketsLinkWholesaleAndFarmersMarkets&rightNav1=FarmersMarketsLinkWholesaleAndFarmersMarkets&topNav=null&leftNav=WholesaleandFarmersMarkets&page=WFMFarmersMarketsHome&resultType=&acct=frmrdirmkt

Subsistence Farming

by Kathryn Doornbos

![[whitemediaspin+march+21+2009.jpg]](blog_clip_image002_0003.jpg) Just a two-weeks ago the Obama’s made headlines by planting the first vegetable garden on White House grounds since WWII. Reporters could have remarked about the historical significance of the first African American First Lady sinking a shovel deep into a property that was built and, for many years, sustained by slave labor. But most didn’t. They focused upon the novelty of the garden itself (New York Times). It is remarkable that such an event is newsworthy to begin with. Since when did planting a vegetable garden warrant a front page article of the New York Times? Such media attention speaks volumes about how far removed American culture is from agriculture. Somehow, the concept of growing and cultivating sustenance for your family has become extraordinary.

Just a two-weeks ago the Obama’s made headlines by planting the first vegetable garden on White House grounds since WWII. Reporters could have remarked about the historical significance of the first African American First Lady sinking a shovel deep into a property that was built and, for many years, sustained by slave labor. But most didn’t. They focused upon the novelty of the garden itself (New York Times). It is remarkable that such an event is newsworthy to begin with. Since when did planting a vegetable garden warrant a front page article of the New York Times? Such media attention speaks volumes about how far removed American culture is from agriculture. Somehow, the concept of growing and cultivating sustenance for your family has become extraordinary.

Subsistence farming wasn’t always this novel. In fact, for the vast majority of agricultural history it was the most direct and simple means to feed one’s family. Ever since humans settled in the Nile River Valley people sustained themselves from what they could grow on their own land, it was a matter of life or death. Eating food that you are not intimately attached to by means of killing, cultivating, or foraging is a fairly new concept in the spectrum of history. In the American South, the trend towards agribusiness in lieu of subsistence began during Reconstruction. Before that time, rural families provided the vast majorities of their foodstuffs for themselves. Subsistence farming served as an alternative to share-cropping for some, but in most cases it was practiced because there was no other choice. In this era the average farmer supported 3-5 individuals with their food production. By the mid-1930s, the average farmer was supporting approximately 25 individuals. Today a single farmer supports an astounding 200 people (Institute). (This number takes into account only food products grown in the United States. If we were to factor in the globalized farming market, one farmer would support as many as 800-1000 people). In less than two centuries, we have drastically changed the nature of agriculture and our means of sustainment. Certainly, this change have fostered a new era of convenience and variety. But what have we lost in the transition?

Principally, we have lost cultural awareness of the origins and means by which our food is produced. Subsistence farming requires a family to live in harmony with their surroundings, working with the earth to cultivate a relatively constant supply of sustenance. It requires acute knowledge of the place where one lives and consistent, dedicated physical labor in order to flourish. Our grocery fueled lifestyle antagonizes all that subsistence supports. We defy the laws of seasonality and freshness by carting fruits and vegetables thousands of miles from farm to supermarket. We forget the man hours and nuances required to raise a vine-ripened tomato. We can disengage from the places where we live and, instead, rely upon the mythical notion that place is irrelevant. As Barbara Kingsolver points out at the beginning of her novel, the fact that a place like Tucson, Arizona, a city surrounded by a desert whose water is supplied by a pipeline, even exists is testament to our disengagement from the importance of place (Kingsolver 32). For eons cities flourished only where the perfect combination of fertile land, ample water, and protective landscapes collided. Today we coax them out of nothingness. Maybe that’s okay, but I find it disconcerting.

On a more philosophical level, we have lost a degree of personal sovereignty. We are independently and culturally so deeply invested in large-scale agribusiness that, I can safely say, the majority of Americans wouldn’t know how to grow, forage, or kill their own food. Culturally, these skills are stigmatized as unnecessary and primitive. Personally, they rank as markedly uncomfortable compared to the ease of air-conditioned supermarkets and drive-thru restaurants. Fair enough. But at some point convenience subsides to helplessness. As one of the three necessities for existence (water and 02 completing the triage) food is a critically important aspect of life. Yet most of us have relinquished the responsibility and knowledge of its production to some ‘other’ person(s), whom in most cases, we have no personal connection with. We take for granted that tomorrow there will be produce in our grocery stores and kitchens without personally ensuring that it occurs

Of course, growing one’s own food is a time consuming, labor intensive, and difficult business that America people could not possibly undertake with any success… or is it? Historical evidence says otherwise. In the 1943, with food shortages taking hold and a war at looming, Eleanor Roosevelt called on Americans to plant Victory Gardens as she herself planted one on the White House lawn. In a single season, 25 million home gardens were planted and 40% of the produce that American’s consumed was grown in these very gardens (Chicago Tribune). Partial subsistence is easily customized for just about any living and socio-economic position you might occupy. In the weeks following the new White House garden, national seed companies have seen sales increase by “25-30%” compared to last year (CNN). Perhaps, as a nation, we are realizing that, in the spirit of a well-known Cree proverb, “we cannot eat money.” Subsistence farming shouldn’t be extraordinary or news-worthy; it should be an everyday practice in maintaining a connection with the food we eat, the place we live, and the last shreds of personal sovereignty society affords us.

Works Cited

Kingsolver, Barbara. Animal, Vegetable, Miracle: A Year of Food Life. New York: Harper Collins, 2007.

“'Recession gardens trim grocery bills, teach lessons” CNN April 1 2009 http://www.cnn.com/2009/LIVING/04/01/recession.garden/

“Obamas to Plant Vegetable Garden at White House” March 19th, 2009 New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/20/dining/20garden.html

“Establishing Land-Grant Universities” Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University

of Florida www.ifas.ufl.edu/land_grant_history/events.html

“2009 Victory Garden” March 1st, 2009. Chicago Tribune.

http://archives.chicagotribune.com/2009/mar/01/opinion/chi-perspec0301gardenmar01

Aunt Jemima

by David Loos

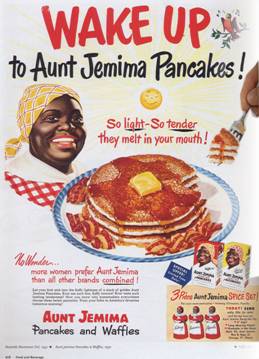

Aunt Jemima has been a prominent symbol in American culture for more than 115 years. In 1889, Christ Rutt and Charles Underwood of the Pearl Milling Company developed the first pancake ready-mix. They used Aunt Jemima as their logo. Tina Gianoulis explains that the image preceded the product: “Based on the pre-Civil War stereotype of the fat, jolly, no-nonsense black ‘ mammy,’ the character of Aunt Jemima was first introduced in a minstrel show in the late 1800s called ‘The Emigrant.’“ Gianlouis suggests that “the image of the kind and funny black mammy was comforting and safe to many white consumers.” Aunt Jemima Pancake Ready-Mix was paired with the soothing image of a mammy figure, and the overwhelmingly popular image aided the growth of the Pearl Milling Company, which was eventually renamed the Aunt Jemima Mills Company in 1914.

mammy,’ the character of Aunt Jemima was first introduced in a minstrel show in the late 1800s called ‘The Emigrant.’“ Gianlouis suggests that “the image of the kind and funny black mammy was comforting and safe to many white consumers.” Aunt Jemima Pancake Ready-Mix was paired with the soothing image of a mammy figure, and the overwhelmingly popular image aided the growth of the Pearl Milling Company, which was eventually renamed the Aunt Jemima Mills Company in 1914.

Disappearing boundaries of time, space, and money allowed many families across the nation to acquire certain commodities, such as Aunt Jemima products, that would make the average American’s life a little easier. The first ready-mix was made from wheat, corn, rye, and rice flour. The ingredients’ availability, cheap production costs, and bulky supply provided families with a simple source of sustenance. However, critics have argued over the cultural implications of the Aunt Jemima products for about as long as the product has been in existence.

In Building Houses Out of Chicken Legs, Psyche Williams-Forson emphasizes how black women were not “a threat to white men’s virility and white women’s bodies, a white man’s own desires for black and white women’s bodies notwithstanding” as opposed to a black man in a domestic setting that could be in direct contact with vulnerable white women (38). She further analyzes “how power can be present in even the most mundane objects of our material lives” (49). Her insights provide a basic understanding of the empowering historical connotations that were applied to many images, especially Aunt Jemima, and how these implications led to contradicting and oversimplified definitions of the African American community as a whole.

John Stuart, President of the Quaker Oats Company, purchased the Aunt Jemima Mills Company in 1926 as a strategic marketing move that would further enhance the company’s ability to supply the increasingly fast-paced nation with more convenience products. “One of Aunt Jemima’s more important historical functions,” Doris Witt explains, “has surely been to obscure just such ideological contradictions stemming from the exploitation of assembly-line labor in the development of US consumer capitalism-the exploitation, moreover, of a heavily immigrant female labor pool whose boundaries were policed though the continual renegotiation of the color line” (38).

Nancy Green, Anna Robinson, Aylene Lewis, and Gladys Knight were all spokeswomen for the Aunt Jemima products, and they all represented physical manifestations of the figurative connotations that have been applied to Aunt Jemima as a “mammy” figure. In a way these women have caused the historical implications of Aunt Jemima as an exclusively racist figure to be a persistent ideology in American culture in the late 19th and the 20th centuries. A subtle theme can be applied to the Aunt Jemima figure: the white superficiality of power over blacks and the depth of black superiority in the plantation kitchens. This is an example of the historical context that has resonated through the ages and sustained itself through the representative “mammy” spokeswomen for Aunt Jemima products.

In 1937, the Aunt Jemima symbol was copyrighted as a trademark by the Quaker Oats Company. After the symbol was trademarked, numerous advertisements and campaigns were launched to promote the Aunt Jemima products. Some advertisements “began ‘showing kids and moms making not just pancakes but, ‘Aunt Jemimas’” (The Quaker Oats Company). Nearly all of these advertisements depicted only whites in domestic settings, but the images still captured the recurring power struggle between whites and blacks simply by the lack of an African American in the ad regardless of the fact that these white families were relying upon Aunt Jemima for sustenance.

Doris Witt explains how the connotations the Aunt Jemima symbol implied began to change in the 1960s. African Americans began to change their view of the icon and drew strength from a masculine and rebellious Aunt Jemima. The changing perceptions of Aunt Jemima generally led to ambiguous meanings being interpreted by the icon, and subsequent years of African American outrage at the persistence of this image would cause the Quaker Oats Company to update the symbol. In 1989, Aunt Jemima got a total makeover by removing her headband, adding pearl earrings, making her a fashionably thin woman, and hiring Gladys Knight as the new spokeswoman. This image alteration “a response from the Quaker Oats Company who knew many African Americans viewed the image as an insulting glorification of slavery,” (Gianoulis) and the company wanted to appease an outraged African American community. Aunt Jemima’s head was adjusted into a more upright position in 1992, and this alteration can be interpreted in many different ways, but not many critics have elaborated upon it due to the significance of the major change three years earlier.

There is a persistent metaphorical battle that has been centered around the image because this one image has continually illustrated “the ways black people disrupted the hegemonic cultural assumptions that tried to define them” (Williams-Forson 69). The Aunt Jemima icon serves as “an ideal medium for examining the confluence of social relations, where the values, traditions, mores, and enduring historical linkages of black life are cultivated and preserved” (Williams-Forson 91). While many critics have stated that the image of Aunt Jemima is inherently racist due to the historical context that must be applied to it, most Americans would probably view the Aunt Jemima logo as a familiar brand of food that simply tastes good. But by countering the interpretations of Aunt Jemima as a racist icon, the prejudiced undertones of the African American history are ever-present in the different interpretations, or lack thereof, of the iconic “mammy” figure. While historically conscious consumers may attempt to ignore the discriminating context forever intertwined with Aunt Jemima, the persistence of this “mammy” image only serves to reinforce modern stereotypes of African Americans.

Works Cited

Gianoulis, Tina. "Aunt Jemima." Bowling, Beatniks, and Bell-Bottoms: Pop Culture of 20th-Century America. Eds. Sara Pendergast and Tom Pendergast. Vol. 1: 1900s-1910s. Detroit: U*X*L, 2002. 2 pp. 5 vols. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Gale. March 6, 2009. <http://find.galegroup.com/ips/start.do?prodId=IPS>.

The Quaker Oats Company. "Aunt Jemima's Historical Timeline." Our History. 2009. The Quaker Oats Company. 6 March, 2009 <http://auntjemima.com/ aj_history/>.

Williams-Forson, Psyche A. Building Houses Out of Chicken Legs. University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

Witt, Doris. Black Hunger: Soul food and America. University of Minnesota Press, 2004.

Leah Chase

by Erin Garner

Leah Chase is the executive chef and, with her husband, co-owner of Dooky (pronounced ducky) Chase restaurant in New Orleans, Louisiana. She is known as the Southern chef of New Orleans and has fed tourists, celebrities, political leaders and New Orleans residents in the fifth ward for over sixty years. She has also authored three cookbooks and has been featured in many others. In 2000, she hosted a national PBS cooking show, “Cooking with Leah.” Her restaurant is famous for many things: its place in civil rights history, the art collection inside, and, of course, Leah’s Creole cooking.

She was born in Madisonville, Louisiana, a rural area near the northern  side of Lake Pontchartrain in 1923. Because the town had no Catholic high schools for black children and Chase’s famiy wanted her to attend a Catholic school, she moved to New Orleans at age 14 to live with an aunt and attend high school at St. Mary’s Academy (Grayson). After graduation, she worked at Colonial Restaurant in the French Quarter—her first taste of the restaurant business. She married Edgar “Dooky” Chase II in 1945. Shortly thereafter, she started working at his parents’ restaurant, first as a hostess. She gradually assumed more responsibility in the business, altering the menu to better reflect her Creole heritage (Global Gourmet, History Makers).

side of Lake Pontchartrain in 1923. Because the town had no Catholic high schools for black children and Chase’s famiy wanted her to attend a Catholic school, she moved to New Orleans at age 14 to live with an aunt and attend high school at St. Mary’s Academy (Grayson). After graduation, she worked at Colonial Restaurant in the French Quarter—her first taste of the restaurant business. She married Edgar “Dooky” Chase II in 1945. Shortly thereafter, she started working at his parents’ restaurant, first as a hostess. She gradually assumed more responsibility in the business, altering the menu to better reflect her Creole heritage (Global Gourmet, History Makers).

Dooky Chase restaurant began as a stand selling homemade po’boys and lottery tickets. By the time Leah began working there in 1946, it had become a sit-down establishment. Though the restaurant boasts her husband’s name on the door, Leah does all the cooking and Dooky keeps the books (Global Gourmet). However, she has had no classical training as a chef—her recipes are only inspired by her family’s meals and her Creole heritage. She does not measure her ingredients, cooking instead by relying on the look and texture of her dishes. Despite her lack of training, she is considered one of the best chefs in the nation, particularly in the South. She does not delegate much in her kitchen, preferring to be as hands-on as possible.

One of Chase’s signature dishes at Dooky Chase is gumbo z’herbes, served once a year on Holy Thursday. Traditional gumbo z’herbes recipes are meatless because of Catholic Lenten traditions, and the gumbo is rarely served outside of Lent. Chase’s, however, contains several types of meat. Recipes for gumbo z’herbes call for anywhere from five to fifteen different types of greens (Chase’s uses nine), but traditional cooks always use an odd number of greens to bring good luck. Simpler recipes are quite different from traditional gumbo, and many do not call for any sort of thickening agent, such as okra, roux or file. Some are not even served with rice (McGreger). The gumbo z’herbes at Dooky Chase, however, includes file and is served over rice. Though her recipe breaks traditions, Chase is largely responsible for keeping gumbo z’herbes alive. Before she started preparing the dish in her restaurant, the tradition had nearly disappeared from Louisiana’s culture. Many who still prepare it are older people, like Chase herself.

Dooky Chase is home to artwork from many notable African-American artists, many living in the New Orleans area. Chase began her art collection by simply hanging posters of fine art prints around her restaurant in the 1970s (MacCash). When she first began collecting original works, Chase would often trade meals for paintings. As her collection and her restaurant grew, she transitioned to paying artists with money instead of food. She has served on the boards of directors for several New Orleans arts and cultural establishments and is a lifetime trustee of the New Orleans Museum of Art. She has even spoken before Congress in favor of greater funding for the National Endowment for the Arts. Some art critics and other collectors have said the collection at Dooky Chase is the best collection of African-American art in the country.

More impressive than the art collection, however, is Dooky Chase’s history as part of the civil rights movement. During the 1960s, activists groups would gather to talk about the civil rights movement and eat Creole cuisine at Dooky Chase. People of different races would come to the restaurant and talk about strategy—where should they hold their next sit-in? How difficult would it be to protest in a certain location? Though such meetings were illegal, the restaurant was so popular that police left the situation alone. Though Chase did not participate in the meetings, her role in the civil rights movement was an important one: preparing food to serve to activist groups while they met (Shaban). Many civil rights leaders, including Thurgood Marshall and Martin Luther King, Jr., along with countless other lesser-known activists, dined at Dooky Chase during the height of the civil rights movement. The restaurant continues to be a political meting ground (Jenkins).

African-Americans were a lucrative market during the age of segregation—restaurants serving blacks were rare. Few blacks dined out; many did not even really know what restaurants were about (Jenkins). Restaurants like Dooky Chase, serving both whites and blacks, were even rarer. Chase’s restaurant was ahead of its time according to social regulations (not to mention laws prohibiting integrated dining). She built a reputation for herself as a civic leader, a position that brought her surprising popularity among even the wealthiest circles of whites, who became her patrons in the post-civil rights era (Elie). Dooky Chase was one of the first New Orleans restaurants to surpass cultural barriers that pushed people away from certain establishments.

Chase has also served notable guests, including Duke Ellington (who convinced Chase to serve his favorite beer, Heineken), Ray Charles, Nat King Cole, Louis Armstrong, Lena Horne, and President Barrack Obama during his presidential campaign (Global Gourmet). For her community involvement with the arts and her role in the fight for civil rights, Chase has earned several prestigious awards, including the Loving Cup Award in 1997 from the New Orleans Times-Picayune, the Outstanding Woman Award from the National Council of Negro Women and a series of NAACP awards.

When Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans in September 2005, Dooky Chase filled with five feet of water. Because the restaurant is a historically significant part of the city and a special place for many residents, other members of the New Orleans restaurant community helped 86-year-old Leah reopen her restaurant. Other restaurateurs hosted a benefit in the French Quarter to raise money for Dooky Chase to reopen, complete with Leah’s gumbo. Their efforts raised over $60,000 to help the Chases reopen their establishment in 2007. The Southern Foodways Alliance was responsible for much of the fundraising, and Starbucks donated $150,000 toward the renovations (Severson).

In 2007, Chase served a meal to President George W. Bush, a gesture not well received by many in the New Orleans community. Many New Orleans residents, including Chase herself, were living in FEMA trailers in neighborhoods still devastated by Hurricane Katrina. Many felt as though the federal government had not taken enough action toward rebuilding the city and saw Chase’s service to the president as a betrayal.

Leah Chase wears many hats—chef, business owner, civil rights leader and art collector, among others. She is an unofficial ambassador for the city of New Orleans and one of the city’s most loved residents. Her legacy is large, and she is famous beyond the culinary world. For over 60 years, she has been serving up some of the best food in Louisiana and much, much more.

Leah Chase’s Gumbo Z'herbes

1 bunch mustard greens

1 bunch collard greens

1 bunch turnip greens

1 bunch watercress

1 bunch beet tops

1 bunch carrot tops

1/2 head of lettuce

1/2 head of cabbage

1 bunch spinach

3 cups onions, diced

1/2 cup garlic, chopped

1 1/2 gallons water

5 tablespoons flour

1 pound smoked sausage

1 pound smoked ham

1 pound hot sausage

1 pound brisket, cubed

1 pound stew meat

1 teaspoon thyme leaves

Salt and cayenne pepper to taste

1 tablespoon file powder

Clean greens under cold running water, making sure to pick out bad leaves. Rinse away any soil or grit. The greens should be washed 2 to 3 times. Chop greens coarsely and place in 12-quart pot along with onions, garlic and water. Bring mixture to a rolling boil, reduce to simmer, cover and cook for 30 minutes.

Strain greens and reserve liquid. Place greens in bowl of a food processor and puree or chop in meat grinder. Pour greens into a mixing bowl, sprinkle in 5 tablespoons flour, blend and set aside.

Dice all meats into 1-inch pieces and place into the 12-quart pot. Return the reserve liquid to the pot and bring to a low boil, cover and cook 30 minutes. Add pureed greens, thyme and season with salt and pepper. Cover and continue to simmer, stirring occasionally until meat is tender, approximately 1 hour. Add water if necessary to retain volume. Add file powder, stir well and adjust salt and pepper if necessary.

Serves 8 to 10 over steamed rice.

From the Associated Press.

Works Cited:

Allen, Carol (from the New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture). “2000 Lifetime Achievement Award Winner—Leah Chase.” Southern Foodways Alliance. http://www.southernfoodways.com/hall_of_fame/lifetime/lifetime_awards_chase.html

Elie, Lolis. “A New Orleans Original.” Gourmet. http://www.gourmet.com/magazine/2000s/2000/02/neworleansoriginal

Grayson, April. “Oral Histories: Leah Chase.” The Southern Gumbo Trail. http://www.southerngumbotrail.com/chase.shtml

Jenkins, Nancy Harmon. “Leah Chase, New Orleans; A Lover of Food Who Nurtured a New Orleans Institution.” Cooks on the Map. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C0CE3DD123DF934A15755C0A966958260

“Leah Chase Biography.” The History Makers. http://www.thehistorymakers.com/biography/biography.asp?bioindex=382&category=businessMakers

MacCash, Doug. “Two New Orleans restaurateurs share a taste for fine art and food.” The New Orleans Times-Picayune. http://blog.nola.com/brettanderson/2008/10/two_new_orleans_restaurateurs.html

McGreger, April. “Where the Wild Greens Are.” Grist. http://www.grist.org/advice/daughter/2009/02/26/

Severson, Kim. “Getting Back to New Orleans.” Diner’s Journal: The New York Times Blog on Dining Out. http://dinersjournal.blogs.nytimes.com/2007/03/14/getting-back-to-new-orleans/

Shaban, Bigad. “Leah Chase proud of Obama’s election; remembers restaurant’s role in civil rights movement.” WWLTV: Louisiana’s News Leader. http://www.wwltv.com/topstories/stories/wwl011909tpdooky.ed424dc.html

“Special Feature: Leah Chase, Dooky Chase’s Star Chef.” The Global Gourmet. http://www.globalgourmet.com/food/egg/egg0197/chase.html

Sharecropping

by Jay Hood

Following the ratification of the 13th amendment, the South experienced the sudden creation of an un-employed work force of 4.5 million former slaves, most of whom were illiterate and had no skills other than agricultural cultivation. After the Civil War, southerners still relied on agriculture as their primary source of economic sustenance. Southern landowners employed former slaves along with poor whites to work the land as part of a system that disenfranchised the uneducated laborers by exploiting their ignorance of contract law. By hiring themselves and their families to a land owner, laborers inadvertently tied themselves to the land in an almost inescapable cyclical system of debt. These individuals became what are generally known as tenant farmers. Charles Aiken explains that “three basic types of farm tenants existed in the Southern plantation regions during the century following the Civil War—cropper, share, and cash. A cropper, also called a sharecropper, owned no farm implements or work stock. All that a sharecropper contributed to the production of a crop was labor, including that of his or her family” (Aiken 29-32). Sharecropping quickly supplanted slavery as the South's source of cheap, expendable labor, and the majority of the victims were newly freed slaves.

The system of sharecropping seemed to be a simple way for a destitute farmer to provide for himself and his family. The system appealed to landless laborers because “under customary rental agreements the landlord and the sharecropper split the crop fifty-fifty. Each also paid for half of the fertilizer, insecticide, ginning, and other production costs” for whatever the sharecropper would need to work the land (Aiken 32). Rather than growing food for his family, however, the sharecropper would be required to exclusively grow cotton or another cash crop. If not, “landlords could exploit their right to refuse to renew the lease at the end of the season as a means of exerting pressure on sharecroppers” (Royce 182). At the end of the year, the sharecropper would harvest his crop and give it to the landowner to take to market and sell, and the laborer would receive anywhere between one half and one third of the remaining sum, after the landowner subtracts the cost of supplies. Frequently, the cost of supplies and food purchased in the landowner’s commissary would exceed the value of the cropper’s share. This drove many families into a cycle of inescapable debt, tying them to the land like the slaves they were intended to replace.

This cycle, sometimes called peonage, became increasingly common after cotton declined in value. Having sold for 43 cents in 1866, by 1882 cotton had fallen to 10 cents per pound. Cotton in and of itself is difficult to grow, requiring a long frost-free period, plenty of sunlight, moderate rain fall, and fairly nutrient rich soil. Soil depletion, drought, and poor farming practices significantly reduced the yield per acre. But cotton remained the South's most valuable crop until the boll weevil entered America's cotton belt just prior to the 1920s. Within a few years, the pest cost the South 13 billion dollars in lost crops.

Before the emergence of sharecropping, slaves and other laborers typically ate the same kind of food every day: some kind of corn based food, such as cornbread or cornpone, salted pork or fat back, and molasses. This meager diet provided the workers with barely enough calories to perform the backbreaking manual labor demanded of them. Slaves frequently developed severe vitamin deficiencies and other associated health problems. If there was any group of people who ever came as close to slavery without ever actually being enslaved, it was the sharecropper. Not only was the sharecropper anchored to the land by his contract with the land-owner, but his diet was effectively the exact same as that of slaves. Although they were farmers, most sharecroppers produced very little produce for their own families, so sharecroppers and their families were susceptible to nutritional disorders.

Many sharecropper children became afflicted with  a disease known as Pellagra. Pellagra is a vitamin deficiency disease caused by dietary lack of niacin (B3) and protein, especially proteins containing the essential amino acid tryptophan. Because tryptophan can be converted into niacin, foods with tryptophan but without niacin, such as milk, prevent pellagra. Some of the symptoms of this disease include:

a disease known as Pellagra. Pellagra is a vitamin deficiency disease caused by dietary lack of niacin (B3) and protein, especially proteins containing the essential amino acid tryptophan. Because tryptophan can be converted into niacin, foods with tryptophan but without niacin, such as milk, prevent pellagra. Some of the symptoms of this disease include:

* High sensitivity to sunlight

* Aggression

* Red skin lesions

* Insomnia

* Weakness

* Mental confusion

* Ataxia, paralysis of extremities, peripheral neuritis

* Diarrhea

* Eventually dementia

Given the sharecropper diet of cornmeal, salted pork, and molasses, most children were without the essential vitamins and minerals required for healthy bodily development or a strong immune system. Sharecroppers, who usually did not have cows of their own, would have to purchase milk on credit from a merchant or from their contractor. Whenever the child of a sharecropper became afflicted with pellagra, it would often result in one of two things for the sharecropper's family: the death of the child, or even greater debt (Ngan).

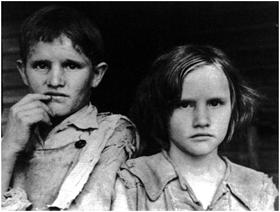

The greatest victims of sharecropping as an institution were not the laborers, but their children. Often made to work in the field with their  fathers and mothers, these undernourished and drastically undereducated children became a part of this cycle of destitution. Without any knowledge of any practice beyond farming, the children of sharecroppers would all too often become sharecroppers themselves. They grew up in shacks where they slept in close proximity to their siblings and parents, without privacy, warmth, or cleanliness. The building would likely consist of little more than a large, single room, with bed, table, fireplace, and, if the family was fortunate enough, a stove. An outhouse, more similar to a latrine than anything else, would be the family's restroom.

fathers and mothers, these undernourished and drastically undereducated children became a part of this cycle of destitution. Without any knowledge of any practice beyond farming, the children of sharecroppers would all too often become sharecroppers themselves. They grew up in shacks where they slept in close proximity to their siblings and parents, without privacy, warmth, or cleanliness. The building would likely consist of little more than a large, single room, with bed, table, fireplace, and, if the family was fortunate enough, a stove. An outhouse, more similar to a latrine than anything else, would be the family's restroom.

As a cultural institution, sharecropping all too effectively demonstrates the way in which poor, desperate people can be victimized by the dubious and wealthy into a system of debt peonage that makes any sort of improvement in the lives of the impoverished impossible. Along with slavery, sharecropping is an example of the ways in which the greed of a few can lead to the suffering of many.

Works Cited:

About Sharecropping. The University of Illinois. February 28. 2009.

http://www.english.illinois.edu/maps/poets/a_f/brown/sharecropping.htm

Aiken, Charles. The Cotton Plantation South. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 1998.

Encyclopedia of Alabama: Sharecropping and Tenant Farming in Alabama. February 25, 2009.Encyclopedia of Alabama. February 28, 2009.http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/face/Article.jsp?id=h-1613

Evans' Images for “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men”. University of Virginia. February 28, 2009.http://xroads.virginia.edu/~UG97/fsa/gallery.html

Pellagra (vitamin B3 or niacin deficiency). March 18, 2008. Vanessa Ngan. New Zealand Dermatalogical Society Incorporated. March 18, 2009.

<http://dermnetnz.org/systemic/pellagra.html>

Royce, Edward. The Origins of Southern Sharecropping. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993.

Farm Security Administration Photographs

by Carl Lewis

“Eat something––even if you’re not hungry––because you never know when you might get hungry, and you don’t know what it’s like to be hungry” my great-grandmother Nonnie used to tell me as a boy. Even as a stubborn and picky kid of the consumer-driven 1990s, I dared not question Nonnie. She knew what she was talking about. Nonnie had suffered through her fair share of hunger growing up as the eldest daughter of a penniless Georgia sharecropper in the Depression-era South, and I’d heard all the family stories to prove it.

Nonnie’s story is nothing unique, however. It’s just one of the thousands of stories of a vast epidemic of southern rural poverty in the 1930s that left one-third of the nation “ill-housed, ill-clad, and illnourished," in the words of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's second inaugural address. The economic crisis in the South was not simply a product of the Great Depression. External factors, including the growth of farm tenancy and sharecropping and widespread infertility of the soil caused by the irresponsible long-term growing of cash crops, put families across the South in dire economic straits. In fact, by 1920, more than 80 percent of southern farmers were left farming someone else’s land, making very little money doing it (Godden 10).

For the better part of the early twentieth-century, mainstream America mostly overlooked the South’s economic problem. Instead, Americans generally bought into what historian Sidney Baldwin calls the “agrarian myth” that “tended either to deny the existence of poverty altogether, or to explain it away” (Baldwin 22). In simpler terms, most Americans mistakenly held the opinion that “the South did not have poor people; it had farming people, and farming people could never truly be poor” (Ownby 1). As books documenting rural poverty like Erskine Caldwell’s Tobacco Road and John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath became popular on a national level, however, the region’s widespread impoverishment came into clearer focus. Diagnosing the South as the “nation’s number one economic problem” (Godden front cover), F.D.R. formed the New Deal agency called the Resettlement Administration in 1935, which was later renamed to the Farm Security Administration in 1937. The Administration’s primary goal was to put the South back on its feet by making loans to individual farmers and constructing planned suburban communities (“FSA-OWI: About the Collection” n. pag.).

To document the progress of the Administration’s various revitalization efforts, the FSA commissioned a team of roughly twenty photographers, led by Roy Stryker, assigned on location across the South. As FSA photographer Arthur Rothstein later recalled, "It was our job to document the problems so that we could justify the New Deal legislation that was designed to alleviate them" (Poska I). In a short matter of time, however, the project’s balance shifted from this intended bureaucratic purpose towards the loftier goal of “introducing America to Americans” (Gorman 3). In other words, Stryker and his unit took on a social mission to rid the South of tenancy and ignorance by calling the nation’s attention to the problem. As photographer Jack Delano reflected, “There were many wrongs in our country that needed righting, and I for one believed that my photographs would help to right them” (Kidd 27).

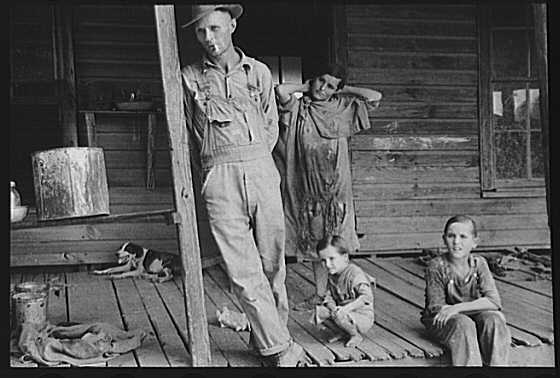

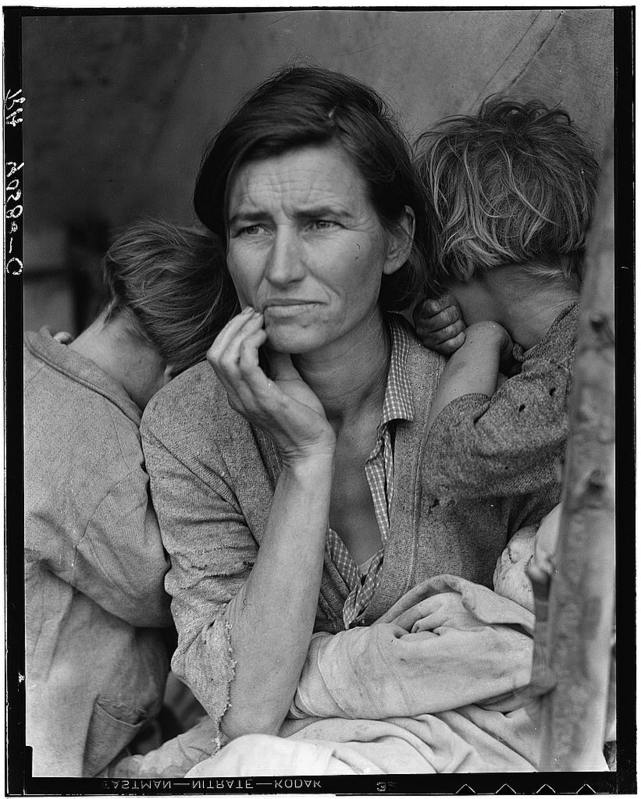

Most of the more than 164,000 black-and-white photographs taken by the FSA from 1935-1942 depict the immense poverty, hunger, and destitution of rural sharecroppers and tenant farmers. Capturing a seemingly objective condition through a subjective lens, FSA photographers were in fact artists whose pictures told a story. Dominated mostly by photos of white southern families barefoot in ragged clothing, surrounded by filth and debris, eating only cornbread and biscuits, the primary goal of the FSA file was to highlight the immense poverty of rural people. The 1936 portrait of the family of Floyd Burroughs, an Alabama cotton  sharecropper, perfectly depicts the image of destitution that characterized most of the FSA collection. Pictures like this one of the Burroughs family seemed to offer a cry for help directed towards the rest of the country.

sharecropper, perfectly depicts the image of destitution that characterized most of the FSA collection. Pictures like this one of the Burroughs family seemed to offer a cry for help directed towards the rest of the country.

The framing and nature of many of the more prominent photos in the collection suggests they were obviously staged. Most FSA photographers had little problem exercising this sort of artistic freedom. They felt the nobility of their mission justified it. As Kidd argues, “most seemed to have felt that the benign nature of the New Deal’s rural uplift programs coupled with their own sincerity of purpose were adequate justifications for their work” (Kidd 29). Often, FSA photographers only paid attention to the most shocking of situations, so as to dramatize the depravity of the rural condition. Again, photographers felt this was a reasonable creative license since they were, after all, giving “voices” to those whose plight had largely gone unnoticed. Some scholars have criticized the photographers’ actions, however, claiming that any “voice” whatsoever given to southerners only came from the photographer, or “ventriloquist,” dictating what that voice would be (Kidd 30). Further, photographers for the FSA tried so hard to capture the essence of southern poverty––often merely to impress Stryker––that they failed to take into account the lived realities of their subjects. Siobhan Davis notes that they “neglected the experiential and regional diversity of those they imaged” (Davis 49). Not unlike what Ernest Matthew Mickler did with his unlicensed use of a picture of a farm woman on the cover of his cookbook White Trash Cooking, FSA photographers simply assumed rural southerners had no problem being photographed in their depraved conditions when many of them held serious reservations about the FSA’s documentary work. As Kidd puts it, they were often “unwilling specimens and reluctant icons” (Kidd 31). In fact, in at least one instance, the subject of an FSA photograph spoke out against the unpermitted use of her image in a negative and inaccurate light. Mrs. Reed, the woman captured in photographer Dorothea Lange’s famous “Migrant Madonna” portrait,  filed suit against the Curtis Publishing Company in 1939 for the publication of her image in the Saturday Evening Post (Kidd 40).

filed suit against the Curtis Publishing Company in 1939 for the publication of her image in the Saturday Evening Post (Kidd 40).

Conspicuously absent from much of the FSA’s collection are pictures of African-Americans. While the collection does provide a brief glimpse into black southern life during the 1930s, it focuses much more heavily on white poverty than it does black life. In her book Building Houses Out of Chicken Legs, Psyche Williams-Forson points out that even when African-Americans are portrayed in FSA photographs, the manner in which they are presented often plays into racial stereotypes. For example, a search of the FSA’s collection on the Library of Congress website yields only 23 results for the term “negro eating.” When the term “negro cooking” is entered, however, 138 results are returned. The considerable amount of pictures of African-Americans preparing food in comparison to consuming food perpetuates the stereotype that blacks belong in the kitchen, not the dining room. To compound the problem, only a small handful of the FSA photographs accomplish anything in the way of speaking out against racial injustice and violence. As historian Nicholas Natanson comments, “If the shadow of poverty hung heavily over blacks in the FSA file, the shadow of terror was all but nonexistent” (Apel 155).

However one wishes to view the FSA file––as either exploitation and overgeneralization or beatification and idealization of the southern underclass––one thing remains true: The images captured by the Farm Security Administration provide a lasting portrait of a people in hardship, a portrait that still contributes to many popular conceptions today.

Works Cited

Apel, Dora. Imagery of Lynching: Black Men, White Women, and the Mob. New Brusnwick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2004.

Baldwin, Sidney. Poverty and Politics: The Rise and Decline of the Farm Security Administration. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1968.

Davis, Siobhan. “Not Readily Visualized by Industrial Workers and Urban Dwellers: Published Images of Rural Women from the FSA Collection.” Reading Southern Poverty Between the Wars. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2006.

“FSA-OWI: About the Collection.” Library of Congress FSA Database. <http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/fsahtml/fabout.html>.

Godden, Richard and Martin Crawford. Reading Southern Poverty Between the Wars. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2006.

Gorman, Juliet. “The History of the Farm Security Administration.” Oberlin College. 2001. <http://www.oberlin.edu/library/papers/honorshistory/2001-Gorman/FSA/

FSAhistory/fsahist3.html>.

Kidd, Stuart. “Dissonant Encounter: FSA Photographers and the Southern Underclass, 1935-1943.” Reading Southern Poverty Between the Wars. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2006.

Ownby, Ted. “Three Agrarianisms and the Idea of a South Without Poverty.” Reading Southern Poverty Between the Wars. The University of Georgia Press: Athens, 2006.

Poska, Allyson M. “Every Picture Tells a Story.” American Social History Project. 2005. <http://chnm.gmu.edu/fsa/>.

Mammies

by Eleta Andrews

The mammy archetype takes form in many mediums, but in all of them, her visage remains the same. In Mammy: A Century of Race, Gender, and Southern Memory, Kimberly Wallace-Sanders lays out a definition of the mammy, “Mammy’s body is grotesquely marked by excess: she is usually extremely overweight, very tall, broad-shouldered; her skin is nearly black. She manages to be a jolly presence—she often sings or tells stories while she works—and a strict disciplinarian at the same time. First as a slave, then as a free woman, the mammy is largely associated with the care of white children or depicted with noticeable attachment to white children” (Wallace-Sanders 6). Other common attributes include loyalty, deep God-fearing principles, and a general lack of sexuality. Significantly, this archetype rose to prominence in the mid-1850s, which was the tail-end of the antebellum period. This is significant because the survival of the mammy archetype depends greatly on distorted southern memory, rather than documented history, for its recognition to continue. The history and understanding of the mammy is most accessible through her appearances in entertainment, marketing, politics, and myth.

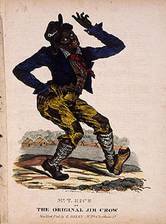

Most scholars place mammy’s origin in 1852, which is the publication date of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Stowe’s character, Aunt Chloe, is an early prototype of the mammy archetype. After the novel’s popularity subsided, the mammy figure begins to appear in other forms of literature. In the Nadir period (1876-1915), mammy appears on postcards and in minstrel shows. In these minstrel shows, the mammy figure becomes exaggerated and even more defemininized. By the 1930s, almost every American would be familiar with the mammy stereotype, and the films Gone with the Wind and Imitation of Life helped burn this image into the American memory. Hattie McDaniel’s portrayal of Mammy was so renowned that she received an Academy Award for her acting work. Some members of the African-American community criticized McDaniel for continually taking roles in which she assumed the mammy character, but she was famous for saying “Why should I complain about making $700 a week playing a maid? If I didn’t, I’d be making $7 a week being one” (Understanding Slavery). McDaniel’s famous quotation is a humorous, yet dark commentary on the lack of options for black women during a dark and confusing time in American history.

Louise Beavers’ role as “Aunt Delilah” in Imitation of Life is doubly significant. As an actress, she often portrayed characters classified as mammies, but in Imitation of Life, Aunt Delilah is a character who is modeled after the “Aunt Jemima” of pancake batter and syrup fame. In the film, Aunt Delilah is a maid for a white family, and the white family makes a great sum of money after marketing Aunt Delilah’s pancake flour recipe with her image. The family becomes very wealthy, but Aunt Delilah explains to the family that instead of taking her share of the money, she would rather continue to stay and work for the family This link is important because the use of the name “Aunt Jemima” is a direct appeal to the mammy stereotype. In minstrel shows, this name was frequently used in scripts for mammy characters. The pancake company began using the name and image in 1890 and hired Nancy Green as the first model depicting Aunt Jemima. The first Aunt Jemima was very dark-skinned and wore an apron and a head scarf. Over 100 years later, the company updated the Aunt Jemima image by lightening her skin, removing the apron and head scarf, adding pearl earrings, and updating her hair style.

In politics, the mammy archetype made headlines in 1923 when a Mississippi senator and a Virginia chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy suggested that a statue commemorating the black mammies of the Old South should be erected and placed in the Capitol building. This idea quickly lost favor by the majority of the legislature, but the suggestion tells a unique story about the exception of the mammy in a time of turbulent race relations. The United Daughters of the Confederacy, a social group which honors the men who fought for the Old South, wanted a statue that revered a double minority: an African-American woman. It is significant, however, that these women wanted to honor the mammy figure as opposed to any other African-American actual person or stereotype; the mammy was loyal, docile, and non-threatening, and she supposedly held together the fabric of the glorified Old South. Wallace-Sanders writes:

Her large dark body and her round smiling face tower over our imaginations, causing more accurate representations of African-American women to wither in her shadow. The mammy’s stereotypical attributes—her deeply sonorous and effortlessly soothing voice, her infinite patience, her raucous laugh, her self-deprecating wit, her implicit understanding and acceptance of her inferiority and her devotion to whites—all point to a long-lasting and troubled marriage of racial and gender essentialism, mythology, and southern nostalgia. (Wallace-Sanders 2)

The idea of the non-threatening mammy has been researched and analyzed by both African-American Studies and Women’s and Gender Studies scholars. Patricia Turner, a prominent historian, suggests that it was very unlikely that black women on slave plantations were overweight, citing food logs and types of labor. She also explains that most black women in the 19th century did not live past their 50th birthday, which nullifies the idea that mammies were common, since their old age would contradict this statistic. Turner and others like her suggest that the image of the mammy was a construction that overturned the earlier image of black women: sexual temptations for their white masters. The large number of mulatto children on plantations juxtaposed with the limited interaction between black women and large numbers of white men suggests that white plantation owners had numerous affairs with slave women. To overcome this taboo topic, black women were either portrayed as young and promiscuous or as the old, unattractive mammy figure. The mammy figure was non-threatening, so this image won favor among whites in the post-Reconstruction Era.

While many scholars label the mammy figure as a myth, the Works Progress Administration narratives suggest that, although this figure has been exaggerated, there were many slave women who took care of white children. By serving as wet nurses and babysitters, some of these women did form bonds with their masters’ children, and this pattern of black women tending white children continued for several generations. The difference is that the existence of mammies in white memory is the image that continued in entertainment, marketing, and politics, all the while becoming more exaggerated and turning one image into the myth that still exists today in pop culture.

Works Cited

Wallace-Sanders, Kimberly. Mammy: A Century of Race, Gender, and Southern Memory. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. 2008.

http://www.understandingslavery.com/citizen/explore/activism/biographies/. Date accessed: February 12, 2009.

http://xroads.virginia.edu/~MA99/diller/mammy/fiction.html. Date accessed: February 12, 2009.

Minstrel Shows

by Drayton Perkins

Following the Panic of 1837, Americans began to redefine the idea of entertainment. In 1843, four men created a form of comedy that would last for several decades and have a huge impact on the future of American entertainment. These men, who referred to themselves as the Virginia Minstrels, traveled the countryside performing for different audiences in blackface. Blackface performances consisted of white men and women who would cover their faces in burnt cork or greasepaint in order to appear black. Their routine was unique at first, but soon other comedic groups picked up on it, and the art of blackface minstrelsy had its start. A typical show had a three-part act during which several different characters would sing and dance around stage making satirical, racist remarks that instilled several stereotypes about the African American race into the minds of all Americans.