White Resistance to Integration in Macon

By Olivia Brayan, James Cummings, Kaylee Faulkner, Tequilla Reid, Phoebe Thiraveja, and Alyssa Williamson

Biography of Mayor Ronnie Thompson

Compared to some southern cities, the civil rights movement in Macon was relatively peaceful, but whites in Macon were committed to white supremacy and the movement faced some resistance.

In a letter to the editor of the Macon Telegraph, a white Maconite defined the color line, saying “I HAVE NOTHING AGINTS THE NEGRO. It’s the ‘white negro’ that makes my stomach crawl.” Charles M. Grant goes on to define the “white negro” as a white man with “black blood” that would rather serve, love and mix with all Negroes. In the next paragraph he further identifies himself as a segregationist stating that “God made man several different colors. If he would have wanted us to mix and disgrace the classes of blood that he created, he would have made us the same color.” Grant is not the only one to voice these complaints and opinions about integration, there are many other just like him with similar or stronger opinions. (Grant, 1963). Resistance to integration in Macon can be found in supremacy groups such as the KKK and in occasional moments of violence.

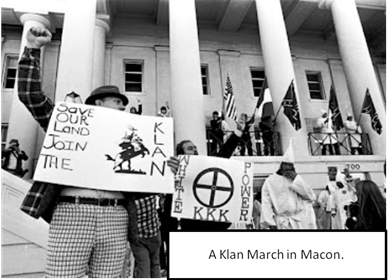

The most promnent white resistance group during the movement was the the Klu Klux Klan. Many whites refused to join Klan due to their use of violence against their “enemies.” For instance, personnel and civilian workers at Robins Air Force Base were not allowed to participate in the burning of a cross at a Klan rally nearby. If one did so, they would have been put under investigation by the Air Force under order of Major General A.V. P. Anderson, Jr., Commander of Warner Robins Air Material Area (Turpin). Not only government personnel stayed out of the mix when it came to acting with that of the Klu Klux Klan, but college students from Mercer University of Macon Georgia also denied compliance with a group that in their opinion was in “direct opposition of every principle of Jesus Christ” (Macon Telegraph July 1950). Many Klan members, however, claimed that their goals were to “to protect the Protestant-Christian faith, to protect the God-given white race, to protect the Constitution of the United States and to protect the woman-hood of this country,” according to the Imperial Wizard E. L. Edwards of Atlanta (Munck).

KKK members held demonstrations in hopes that the community would better understand their platform, but the community would not allow black organizations to demonstrate or allow blacks to vote. In May of 1962 in Macon, a poll segregation case was opened. During this hearing, Judge W. A. Bootle had to determine whether to abolish racial distinctions or ignore the demand of the U.S. Department of Justice. The lawyers involved expected that Bootle to issue an injunction prohibiting local officials from holding their elections on a segregated basis. For this to happen, white supremacists had to fight the government harder for a segment of power in the voting stands (Gorham).

Many people in the community during this time were fighting for their voice to be heard, whether it was the white supremacists participating in large rallies sponsored by the Klu Klux Klan or small monitored meetings scheduled by local activists in the NAACP. Although their voice was strong, the black community faced a serious challenge because many white leaders in Macon were sympathetic to white supremacy.

Earlier in 1962, black Maconites had successfully orchestrated a bus boycott that led to the transit system’s integration. The boycott was mostly peaceful, but violence erupted when a group of white unidentified persons drove to a dance hall on Broadway and fired a gunshot blast into the crowd, wounding two men, Henry Williams and Rudine Ashley. After the shooting, Mayor Ed Wilson sought a way to negotiate between the bus companies and the black leaders to prevent further violence. When fist fights broke out between black and white bus passengers at the intersection of Broadway and Cherry St., Mayor Ed Wilson realized that the violence would continue unless he forced a compromise between the two groups.

His solution was to try to keep the two groups separated while allowing blacks to ride the bus. Though this idea at first seemed reasonable to some of the black leaders, others were distressed because they felt that the issue wouldn’t be solved and that the viciousness would continue. The violence and disturbances to the peace did continue in the form of white youths throwing rocks at passing by black drivers and police arresting congregating blacks on sidewalks.

A black man, Richard Glawson, was also arrested during the Macon bus boycott for carrying a shotgun and some shells around while resisting police arrest. Charges against him were dismissed, but tensions were still high. Another black man reported that that he was beaten by other blacks for trying to board a bus.

As more people took sides during the movement, violence escalated between the opposing sides. Five teenagers placed a bomb in Mayor Wilson’s mailbox because of his policies on integrating Macon’s city parks (Five Youths). Although the bomb did explode in the mailbox, nobody was injured, despite the metal fragments that were scattered up to 100 feet around the bomb’s radius. This incident occurred two weeks after Tattnall Square Park was integrated, and another incident occurred there at that time.

A black man was stabbed in the park a week before the bombing happened. The victim was Louis Wynn, and two white men, I. B. Busbee and Lamar Busbee, were charged with disorderly conduct connected to the stabbing. Mayor Wilson threatened to close the park if the trouble was not halted and he ordered police to patrol the area to keep violence from escalating any further (City Council).

A few days later, a riot erupted in the park. The incident began when a group of Negro and white kids entered the park and started throwing bottles at one another. While this was happening, Billy Randall intervened in the conflict and told the black kids to leave the park. As the kids were leaving the park, a rock throwing battle ensued between white and black youths, and white youths pelted Randall’s automobile with rocks as he drove away.

Later, a black girl attempted to walk through the park, but white teenagers harassed her by throwing their shoes at her. A policeman ushered the girl out of the park and told to leave. That night, a group of black teenagers went into the park and were quickly escorted out by police officers attempting to keep the blacks and the whites separate to avoid confrontation. Though police stayed there for the rest of the night, violence still continued between the two groups.

Violence is not the only form of resistance in Macon. There were politics as well as the opinions and views of the locals and the people in power. While these issues were not prominent in the news and media, the attitude of most white Maconites toward integration was not positive. The whites of Macon manage to keep control of their community through fear tactics and politics, using massive demonstrations of the KKK and select instances of violence to remind African-American’s where they stand, on the other side of the color line.

Works Cited

"Bus Stoning Ends Run on 2 Lines." Macon Telegraph [Macon] 13 Feb. 1962. Print.

"City Council Resolution Urges Closing of Parks If Racial Incidents Continue." Macon Telegraph [Macon] 13 Apr. 1963. Print.

Gilleland, Danny. "A Klan March in Macon." Http://almostinfocus.blogspot.com. 04 June 2008. Web. 26 Apr. 2012.

Golden, Brooks B. "Today in 1962 the Bus Boycott of Macon Georgia Begins." Http://brooksblairgolden.blogspot.com. 12 Feb. 2009 Web. 26 Apr. 2012.

Gorham, Howard. “Judge Bootle Orders Poll Desegregation 6 of 13 Bibb Precincts Must Drop Racial Bars.” Macon Telegraph. June 2 1952. 01A.

Gorham, Howard, and Ken Barnes. "Wilson to Seek End of Boycott." Macon Telegraph [Macon] 21 Apr. 1963. Print.

Grant, Charles M. "Letter to the Editor." Mercer Cluster [Macon] 30 Nov. 1963, 10th ed., 2a sec.: 2a. Print.

“Jurist Says Segregated Polls Illegal.” Macon Telegraph. June 22, 1952. 01A.

“Klan to Parade Minus Masks Here Tonight.” Macon Telegraph. July 14, 1950. 01A

“Klansmen Meet, Fire Cross Here (Bibb).” Macon Telegraph. April 15, 1956. 01A

Morgan, Ray. “Round Table: The People Speak Says Klan's Standards To Be Higher Than Ever.” Macon Telegraph. June 14, 1951. 06A.

Munck, Hal. “Large KKK Demonstration Is Planned Here on July 14.” Macon Telegraph. July 6, 1950. 01A

“Parade Highlights KKK Rally Here.” Macon Telegraph. July 15, 1950. 01A and 06A.

"The Negroes Are United While Whites Are Divided." Macon Telegraph [Macon] 14 Jan. 1957. Print.

Turpin, Bill. “Robins Base Airmen and Civilians Warned About Joining Klan Groups.” Macon Telegraph. November 16, 1956. 01A.

"Two Negroes Shot as New Violence in City Flares." Macon Telegraph [Macon] 17 Feb. 1962, 01A sec. Print.

Tyson, Timothy B. Radio Free Dixie: Robert F. Williams and the Roots of Black Power. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1999. Print

Raymond, John. “Klansmen Fire Crosses, Blast Integrationists.” Macon Telegraph. August 5 1956. 01A.

"5 Youths Admit Placing Bomb in Wilson Mailbox." Macon Telegraph [Macon] 16 Apr. 1963.