St. Peter Claver Catholic Church

By Jane Hammond, Regan Hice, Melissa Mantecon, and Julian Onyekwere

Oral history with Muriel McDowell-Jackson

St. Peter Claver has been on the cutting edge of progression in every era, from its charter as an African American parish, to the present. St. Peter Claver has always taken an active role in the community and continues to do so. Located on Ward Street in Macon, Georgia, St. Peter Claver dates back to 1888, and is considered a historic landmark in the state of Georgia. It has a catholic school, a sanctuary, housing accommodations, specifically for the nuns and fathers, and a recreation facility. It is unusual among parishes in Georgia because its parishioners are primarily African American.

St. Peter Claver was founded as an African American mission parish by the Lyon brothers who founded St. Stanislaus College on Pio Nono Avenue. The church moved to its current location on Ward Street in 1913. St. Peter Claver serves a fully integrated congregation in Pleasant Hill, an African American neighborhood. Unlike many Catholic parishes in the South, the church has always been integrated. In fact, its priests are often foreign missionaries, and its current priests come from Poland and Nigeria.

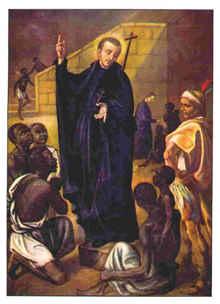

St. Peter Claver is named for the patron saint of negro missions. Peter Claver was the son of a Catalonian farmer, born in the town of Verdu, Spain, in 1581. Peter Claver was a scholar and very serious about his education. Claver was sent to evangelize the people under the Spanish possession in the Americas. He landed in the city of Cartagena, the chief slave port in the New World, in 1610. The slaves were often very ill and mentally unstable as a result of the way they were treated. The Catholic missionaries tried to end slavery by appealing to the Spanish leaders and the Pope, to no avail. The missionaries tended to the slaves, alleviating some of the pain they were feeling  and preaching the Gospel. Peter Claver proclaimed himself “the slave of the Negroes forever” and spent forty-four years ministering to slaves. He treated them with kindness and understanding, acknowledging them as people instead of slaves. During his lifetime as a missionary, he brought over 300,000 Negroes to faith. He was beatified on July 16th, 1850, and Pope Leo XIII canonized him on January 15th, 1888.

and preaching the Gospel. Peter Claver proclaimed himself “the slave of the Negroes forever” and spent forty-four years ministering to slaves. He treated them with kindness and understanding, acknowledging them as people instead of slaves. During his lifetime as a missionary, he brought over 300,000 Negroes to faith. He was beatified on July 16th, 1850, and Pope Leo XIII canonized him on January 15th, 1888.

The ideas and principles that St. Peter Claver applied to his ministry translated to the church. Because the church has been fully integrated since its founding, it did not take an active role in the Civil Rights Movement. They were never cautioned about their institutions, they were never mandated to segregate, and they weren’t even threatened by the Ku Klux Klan or other radical groups. St. Peter Claver kept emphasis on the idea of community. They were a self-sufficient church, and the nuns rarely had reason to venture far from the edges of the church, let alone the neighborhood. As a result, St. Peter Claver has led a relatively quite and peaceful existence with the area. What St. Peter Claver lacked, as far as outstanding notoriety in the civil rights movement, they make up for in the form of community outreach and service to Macon as a whole.

For decades, the nuns of St. Peter Claver would walk the streets of the Pleasant Hill neighborhood, greeting families and looking over the neighborhood surrounding the church. They knew most all of the occupants by name and also ministered to the elderly, unable to leave their homes. They would teach the children, both in and outside the confines of the church and would often eat with the families. It was safe to say that the community surrounding the church was much safer as a result of the networking brought together by St. Peter Claver. Church members, in turn, volunteer to take care of whatever type of renovation, addition, or subtraction that the church needs. The church building has been renovated a number of times, trying to keep up with the architecture of the passing eras, all done by church staff and faculty. A fellowship hall was added, fencing removed, and an area of reflection built, all by volunteers and church hands. St. Peter Claver has also donated parts of its land endowment to promote growth in the community. St. Peter Claver has also begun work, in a coordinated effort to bring restoration to Macon, through involvement with community development, outreach ministry, and interfaith organizations.

School History

St. Peter Claver Catholic School is an educational ministry of the church. The school was founded in 1913 with the help of Mother Katharine Drexel, Bishop Benjamin Kiely, and Father Ignatious LIssner. Bishop Benjamin Kiely hoped to provide a religious and educational foundation for the black community.  Since 1870, an attempt to bring about the Colored Apostolate, but the progression was coming along slowly. He was told from the church hierarchy in Rome that he should call upon for assistance the Society of African Missions to help staff the parish. So on December 17, 1906, Father Ignatius Lissner received a letter offering the pastoral charge.

Since 1870, an attempt to bring about the Colored Apostolate, but the progression was coming along slowly. He was told from the church hierarchy in Rome that he should call upon for assistance the Society of African Missions to help staff the parish. So on December 17, 1906, Father Ignatius Lissner received a letter offering the pastoral charge.

After working on missions in West Africa, Father Lissner was assigned to raise funds among American and Canadians for the mission in West Africa, so he traveled around the U.S., and he saw the dilemma that African American Catholics were facing. Not only were they already few in numbers, but they were also hindered by poverty, religious discrimination, and racism. He went to Rome, where he proposed plans for establishing missions to serve African Americans in Georgia. During the next six years, he established six churches and seven schools in Georgia. The schools include St Benedict the Moor's Church, Savannah (1907), Church and School of Immaculate Conception, Augusta (1908), Hatches Station School (1909), Church and School of St. Anthony, Savannah (1909), St. Mary's School, Savannah (1910), Church and School of Our Lady of Lourdes, Atlanta (1912), Church, School and Convent of St. Peter Claver, Macon (1913). He was also influential in founding a religious congregation for black women, the Handmaids of the Most Pure Heart of Mary. None of these things came easy. Not only was the coldness of the local clergy, and threats from the Klu Klux Klan, there a shortage of funds and staff to maintain these foundations.

Mother Katherine Drexel was born into a wealthy family, but she dedicated her life and her fortune to the order of the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament in 1891, which was devoted to serving Native Americans and African Americans. When she heard word of Bishop Keily, she wanted to be involved as much as possible. Within a few years a new school, rectory, and convent were established at St. Peter Claver. Although Mother Katharine and the sisters in her order where dedicated to abolishing racial injustice, not everyone agreed with their views. The Ku Klux Klan “threatened to tar and feather the white past at one of Drexel’s schools and bomb his church.” The Sisters’ retaliation was to pray and days later, a tornado came and demolished the KKK head quarters, killing two members. A major turning point was in 1969, when the school integrated by allowing white students to attend. The Catholic Church generally refuses to let social problems influence its involvement with religion and its people. They feel the church should offer religious knowledge to everyone that steps forth. The school is a very good indication of it. When most schools where closing their doors to African Americans, St. Peter Claver embraced them.

Mother Katherine Drexel was born into a wealthy family, but she dedicated her life and her fortune to the order of the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament in 1891, which was devoted to serving Native Americans and African Americans. When she heard word of Bishop Keily, she wanted to be involved as much as possible. Within a few years a new school, rectory, and convent were established at St. Peter Claver. Although Mother Katharine and the sisters in her order where dedicated to abolishing racial injustice, not everyone agreed with their views. The Ku Klux Klan “threatened to tar and feather the white past at one of Drexel’s schools and bomb his church.” The Sisters’ retaliation was to pray and days later, a tornado came and demolished the KKK head quarters, killing two members. A major turning point was in 1969, when the school integrated by allowing white students to attend. The Catholic Church generally refuses to let social problems influence its involvement with religion and its people. They feel the church should offer religious knowledge to everyone that steps forth. The school is a very good indication of it. When most schools where closing their doors to African Americans, St. Peter Claver embraced them.

Community Ministry

Both St. Peter Claver Church and School have remained largely outside the civil rights movement. This remains true today, as St. Peter Claver continues its outreach to the community. Catholic outreach to the community is not a foreign concept, as various Popes throughout the centuries have issued their own decrees exalting the virtues of love, kindness, and loyalty to God and the Church. St. Peter Claver Church is in its own right an example of what the Catholic Church has always tried to do for the community.

Unfortunately, for most Southern Catholic churches, full integration and acceptance was a foreign concept. In Andrew Moore’s article, “Practicing What We Preach: White Catholics and the Civil Rights Movement in Atlanta,” he points out that in 1958 Bishop Hyland of Georgia used the Vatican’s desegregation order to formulate a plan to help Georgian Catholic parishes integrate. By gradually integrating schools and churches, no unrest was caused, and churches like St. Peter Claver were used as examples of how and why integration could work. However, in Randall Miller’s discussion of the history of Roman Catholicism in the South, he mentions the fact that most Southern dioceses were wary of integration and were resistant to social change. Nonetheless, Catholic churches and schools integrated faster than those of Protestants and in the public sector.

Perhaps it was the structure of the Catholic Church that lent itself to the successful integration of Southern parishes. Anytime a priest wishes to change parish policies, he must go through several levels of bureaucracy to get his request approved or denied. With Bishops in Atlanta and other areas of the South wishing to show community love and support, surely the higher-ups in Vatican City realized that other outreach initiatives could be achieved through various Papal orders. And at the same time, individual parishes were in command of what happened once decisions from the top were handed down.

This structure provides a background understanding of all of St. Peter Claver Church’s other outreach missions. As Jackson-McDowell said about her childhood priest, “Because of the way the structure was he was the ultimate authority. There was no Parish council or anything else. Anything that was done had to be done on his say so.” This provides insight into how an integrated St. Peter Claver was able to help out the community while the rest of the Southern dioceses resisted. While there are few historical reports of earlier outreaches, Jackson-McDowell recalls several events in her childhood and the present. “We were the ones that started the MLK Annual Breakfast years ago. Our priest was the one along with members of our church that founded Tubman Museum. We had prison outreach when I was a kid … So everyone in the neighborhood knew each other and respected each other, worked together and you know it’s just become a more organized outreach. We have a food pantry, which St. Joseph’s contributes to and so people all in the Pleasant Hill neighborhood come in, and get the foods they need … A lot of things we do we don’t think about them as being special because we’ve always kind of had a foot in that door and now it’s just becoming more formalized and more organized in the community.” Again, the parishioners at St. Peter Claver do not view their church as anything extraordinarily different. They’re just doing God’s work.

This structure provides a background understanding of all of St. Peter Claver Church’s other outreach missions. As Jackson-McDowell said about her childhood priest, “Because of the way the structure was he was the ultimate authority. There was no Parish council or anything else. Anything that was done had to be done on his say so.” This provides insight into how an integrated St. Peter Claver was able to help out the community while the rest of the Southern dioceses resisted. While there are few historical reports of earlier outreaches, Jackson-McDowell recalls several events in her childhood and the present. “We were the ones that started the MLK Annual Breakfast years ago. Our priest was the one along with members of our church that founded Tubman Museum. We had prison outreach when I was a kid … So everyone in the neighborhood knew each other and respected each other, worked together and you know it’s just become a more organized outreach. We have a food pantry, which St. Joseph’s contributes to and so people all in the Pleasant Hill neighborhood come in, and get the foods they need … A lot of things we do we don’t think about them as being special because we’ve always kind of had a foot in that door and now it’s just becoming more formalized and more organized in the community.” Again, the parishioners at St. Peter Claver do not view their church as anything extraordinarily different. They’re just doing God’s work.

As part of their community outreach in 1981, the church hosted a workshop on racism featuring three lecturers. The first was a professor of theology and ethics from Emory University. He spoke about the two segregated churches in America and referenced Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s statement that, “The most racist hour in America begins at 11 a.m. on Sunday.” He went on to add that, “Racism is the most serious theological and ethical problem facing American Christians” (McClary). Sara Mitchell, a teacher from a local school system, also gave a brief history of racism and slavery in the United States and why it needs to be studied to understand racial problems that persisted in a post-Brown v BOE world. Last, Father Richard Keil, who preached at St. Peter Claver at the time, spoke on the roots of racism. He closed his remarks with, “There is so much beauty in the black community, and the same gifts are in the white community. But our goodness is only half, because for so long we haven’t appreciated our other half – our black brothers and sisters. (McClary)” Father Keil helped sponsor the event along with other nuns at the parish. This demonstrates St. Peter Claver’s dedication to helping the community accept and love all of God’s people.

The most compelling outreach currently underway at St. Peter Claver Church is its ministry to the growing Hispanic community. Perhaps outreach is a misnomer, as the church has its own mass in Spanish in its sanctuary every Sunday afternoon. As Susan R. Bales discusses in her book, Religion in the Contemporary South, since the turn of the millennium, the Catholic Church has had an influx of Latino-American members. As Bales observes in her chapter on Southern Catholicism during a visit to a church in North Carolina, little boys and girls with origins from all over the world hold hands and learn about the Bible and Jesus together and not about their perceived differences. While Bales argues that most parishes are trying to find ways to allow everyone to worship together as one Christian unit, the opposite is observed at St. Peter Claver. The mass in Spanish is the last of the day on Sunday. The program for the service is in both Spanish and English but everything spoken is in Spanish. Garces-Foley reminds us that even today, Catholic priests are encouraged to be fluent in at least two languages to best serve their members, and the current priest is no exception. He reads the Eucharist and other parts of the service aloud in Spanish, although church members read the lessons, Gospel, and sermon in Spanish. On a Sunday in April, a local high school student was introduced as being there to assist anyone with questions about the 2010 Census. Other members made announcements about an upcoming soccer league and a bake sale. It’s as though the church outside of the service does not exist. This is not to suggest that this is a bad thing. If anything, it is a way to include Latino-Americans in the parish in a way that does not make them feel ostracized. This is the same path that was taken for blacks and whites at the beginning of St. Peter Claver’s history.

Both St. Peter Claver Church and School have rich histories of accepting things beyond the normal societal standards. By encouraging outreach today through raising money for those starving or encouraging other cultures to celebrate their heritage through their own mass, the church will continue to be a beacon of social equality for other dioceses to follow. And by integrating the school, the school will continue to be a prime example of how the composition of a truly integrated church should look.

Works Cited

- Bales, Susan R. “Sweet Tea and Rosary Beads: An Analysis of Southern Catholicism at the Millennium.” Religion in the Contemporary South. Eds. Corrie E. Norman and Don S. Armentrout. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2005. 191-206. Print.

- Garces-Foley, Kathleen. “Comparing Catholic and Evangelical Integration Efforts.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 47.1 (2008): 17-22. Web. 13 Apr. 2010.

- Jackson-McDowell, Muriel. Personal interview. 23 Apr. 2010.

- Jones, Charles. "St. Peter Claver Church gives $1,000 for starving Africans." Macon Telegraph 21 Nov. 1984: 02B. Print.

- McClary, Gail. "Churches Encourage Racism, Speaker Says." Macon Telegraph 23 May 1981: 06A. Print.

- Miller, Randall M. “Roman Catholicism.” The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Volume 1: Religion. Ed. Samuel S. Hill. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2006. 135-139. Print.

- Moore, Andrew S. “Practicing What We Preach: White Catholics and the Civil Rights Movement in Atlanta.” Georgia Historical Quarterly 89.3 (2008): 334-367. Web. 13 Apr. 2010.

- Osborne, William A. “Chapter Two: The South.” The Segregated Covenant: Race Relations and American Catholics. New York: Herder and Herder, 1967. 43-93. Print.

- Wilder, Larry D. "Church Sets Goal of $13,000." Macon Telegraph 3 Apr 1982: 08A. Print.