The First-Generation of Black Students at Mercer

by Bryant Harden, Alyson Jenkins, Sarah Joyave, Stephen Kearse, and Sarah Wood

Historical Context: Integration of Georgia Universities

In the early 1950’s, a young black girl from Kansas walked one mile to get to the local black school, but the local white school was just down the road. The girl’s father, Oliver Brown, tried to enroll his daughter in the white school, but the school would not allow him to enroll her. Mr. Brown went to court to obtain justice for his daughter. The ruling for Brown vs. Board of Education was issued in 1954, and it marked the beginning of a slow desegregation process in America. Brown vs. Board of Education revealed that separate schools were unequal and depriving the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. It did not require schools to desegregate by a certain time, but it did declare segregation unconstitutional in all schools throughout America (Cozzens 1). The process of integration varied from state to state, but every school has its own tale.

Integration at the University of Georgia was not voluntary. It was achieved through a court order in 1961. However, if it was not for Horace Ward, who was encouraged and inspired by Brown vs. Board of Education, integration at UGA would have been delayed more years than it already was. In 1950, he attempted to enroll in UGA’s law school, but he was rejected. UGA offered to pay for Ward to attend a  law school out of state, but Ward refused the offer, continuing to fight for a spot at the UGA law school. Ward was never accepted, but he eventually attended Northwestern University and returned to Georgia in order to represent two black citizens in a lawsuit to admit them to UGA. On January 6, 1961, Judge William A. Bootle, A Mercer trustee, ruled that the students were fully qualified to be admitted. Hunter and Holmes were admitted to UGA only to find hostile white students determined to keep the university segregated. With the help of the police and support of faculty members, Hunter and Holmes were able to graduate from UGA, completing the university’s integration process (A Brief History). Hunter, Holmes, and particularly Ward responded to discrimination in a persistent, legal manner, setting an example for many black Americans to follow.

law school out of state, but Ward refused the offer, continuing to fight for a spot at the UGA law school. Ward was never accepted, but he eventually attended Northwestern University and returned to Georgia in order to represent two black citizens in a lawsuit to admit them to UGA. On January 6, 1961, Judge William A. Bootle, A Mercer trustee, ruled that the students were fully qualified to be admitted. Hunter and Holmes were admitted to UGA only to find hostile white students determined to keep the university segregated. With the help of the police and support of faculty members, Hunter and Holmes were able to graduate from UGA, completing the university’s integration process (A Brief History). Hunter, Holmes, and particularly Ward responded to discrimination in a persistent, legal manner, setting an example for many black Americans to follow.

Ward returning to Georgia in order to represent Hunter and Holmes demonstrated black citizens’ determination to achieve integration within universities. Joe Hobbs wrote in the Mercer Cluster that the “Movement now must be as a unit…Every effort be directed to helping disadvantaged blacks” (Hobbs 5). Although Ward was not admitted to the University of Georgia himself, he still returned to Georgia to fight for the enrollment of other students like him. He understood the direction in which the Civil Rights Movement was headed, and he was determined to do his part by acquiring equality in the intellectual community.

After UGA’s integration, the Georgia Institute of Technology recognized its inevitable integration and began working to follow the larger university’s example. Georgia Tech announced only a couple months after the University of Georgia’s integration that it too would integrate the following fall. Georgia Tech held true to its word, and it became the first institution of higher education in the Deep South to integrate peacefully and without a court order (Hatfield 1). Emory University, also recognizing inevitable integration, began working to admit a black student into its dental school. The same year that Mercer admitted Sam Oni, Emory admitted its first black student into its dental school (Hatfield 1). Georgia’s larger universities’ integration did not completely eliminate segregation among its colleges and universities. It was not until ten years after Emory’s and Mercer’s integration that Judge Owens issued an order to create a plan to desegregate all institutes of higher learning in Georgia. This order, however, was not carried out into completion until 1988 (Hatfield 1).

Most colleges in Georgia desegregated for reputation’s sake. Institutions realized that fighting integration was a lost cause that only created tension and yielded bad publicity. Despite whites’ protests to their school’s desegregation, Mercer University, the University of Georgia, the Georgia Institute of Technology, and Emory University still chose to admit black students. The black students attending these newly integrated universities responded to their enrollment by fighting for complete equality on campus. They organized clubs and social and academic programs. They threw themselves into involvement, leaving a distinct mark on each university’s history.

Marginalized Black students united together on Georgia campuses by forming groups and organizations such as the Black Student Alliance at Mercer and others at other Georgia schools. UGA, Georgia Tech, Mercer, and Emory all have African-American programs to compensate for the lack of the Black narratives in American history. These universities have also acquired African American clubs, fraternities and sororities. Since the 1960’s and even today, Georgia universities have attempted to promote unity and understanding among races.

Accordingly, Mercer University takes pride in its diverse student population and the fact that with Sam Oni’s admission in 1963, it became one of the first private institutions in the South to voluntarily integrate. Today, after forty-five years of being an integrated school, Mercer has successfully instituted an African American Studies program, black clubs such as the Organization of Black Students (previously known as the Black Student Alliance), and other social and academic organizations. Integration at Georgia schools should not be solely contributed to the universities themselves, but also, perhaps even primarily, to the students who fought for admittance and pushed the universities to change their policies. Because of these students, universities in Georgia can call themselves “fully integrated,” although the definition of “fully integrated” is very speculative.

Race Relations at Mercer: Things weren’t very Dandy

In the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, race was still a tense issue in America and, as Jimmie Samuel—one of the first black students at Mercer—puts it, “Mercer was a microcosm of the country” (Oral history, Jimmie Samuel). Consequently, the students and faculty at Mercer were not exempt to racial tension. Although Mercer integrated in 1963, race relations could not be referred to as ideal.

After the arrival of the first few black students in the 1963-1964 school year, the Mercer admissions team began to scout out other candidates to attend Mercer. According to Jimmie Samuel, “There was a small group in ’65. In ’66 there may have been ten or twelve. In ’67 there was a bigger group of about twenty us. And so when I got here, there may have been 35 or 40 of us altogether” (Oral History, Jimmie Samuel). So Mercer slowly began to diversify its student body. Two important people who contributed to making the transition as smooth as possible were Joe Hendricks and Johnny Mitchell. They went “around the state and other places, interviewing and identifying black students to come” (Oral History, Jimmie Samuel). They wanted to be sure that the black students they brought to Mercer would be able to make the transition both academically and socially. And unfortunately because of race relations the social transition was more difficult than the academic transition (Oral History, Jimmie Samuel).

After the arrival of the first few black students in the 1963-1964 school year, the Mercer admissions team began to scout out other candidates to attend Mercer. According to Jimmie Samuel, “There was a small group in ’65. In ’66 there may have been ten or twelve. In ’67 there was a bigger group of about twenty us. And so when I got here, there may have been 35 or 40 of us altogether” (Oral History, Jimmie Samuel). So Mercer slowly began to diversify its student body. Two important people who contributed to making the transition as smooth as possible were Joe Hendricks and Johnny Mitchell. They went “around the state and other places, interviewing and identifying black students to come” (Oral History, Jimmie Samuel). They wanted to be sure that the black students they brought to Mercer would be able to make the transition both academically and socially. And unfortunately because of race relations the social transition was more difficult than the academic transition (Oral History, Jimmie Samuel).

These black students had been recruited from all over the state and other surrounding areas, but soon after their arrival they had become a very close knit group. Their close friendships were vital during the late sixties and early seventies, when race relations were very tense on campus. The rest of the nation was in turmoil, with violent protest breaking out in the cities and the Vietnam War in development. On other college campuses, race issues were being confronted with student rebellions and violence. Newsweek even had a cover story about students that were brandishing bullet belts, and bringing violent protest to their campuses.

All of these events affected Mercer and the race relations that existed between students and other students, and the students and faculty. Jimmie Samuel said that there were “about ten to fifteen faculty members that were much more liberal than the other faculty and much more liberal than the student body” (Oral History, Jimmie Samuel). He remembers the student body at this time as being “very, very conservative,” so conservative that some students probably even based their decision to not attend Mercer because they had allowed black students to enroll (Oral History, Jimmie Samuel). Although the small group of black students enrolled in Mercer in the late sixties lacked any real type of threatening presence, because of the conservative attitude and tense race relations of the time, many white students were still very uncomfortable with the idea. Although Mercer did have a good idea by voluntarily integrating, that was not the end of the issue. It was clear that the administration supported integration because it accepted the black students, but accepting the black students was only the first step. The administration seemed to wash its hands of the issue, leaving the students to implement the next steps of integration. That is how the Black Student Alliance came to exist

All of these events affected Mercer and the race relations that existed between students and other students, and the students and faculty. Jimmie Samuel said that there were “about ten to fifteen faculty members that were much more liberal than the other faculty and much more liberal than the student body” (Oral History, Jimmie Samuel). He remembers the student body at this time as being “very, very conservative,” so conservative that some students probably even based their decision to not attend Mercer because they had allowed black students to enroll (Oral History, Jimmie Samuel). Although the small group of black students enrolled in Mercer in the late sixties lacked any real type of threatening presence, because of the conservative attitude and tense race relations of the time, many white students were still very uncomfortable with the idea. Although Mercer did have a good idea by voluntarily integrating, that was not the end of the issue. It was clear that the administration supported integration because it accepted the black students, but accepting the black students was only the first step. The administration seemed to wash its hands of the issue, leaving the students to implement the next steps of integration. That is how the Black Student Alliance came to exist . Black students knew it was their responsibility to finish the arduous task of integrating.

. Black students knew it was their responsibility to finish the arduous task of integrating.

Some of the ways the black students challenged the university was through their protests over the student center’s hours, the pushing for an African American studies program, and responding to prejudice in the Cauldron. These protests were organized and possibly incendiary, but they were necessary to incite change. The Black Student Alliance decided to protest the 1969-70 Cauldron because they were not given any space in the yearbook, unlike every other student organization. Black students were not being recognized for their involvement and their leadership across campus like other student organizations. So with the destruction by fire (outside) of several yearbooks, and their display of these yearbooks in the student center, people took notice, and the BSA was given some space in the Cauldron of 1970-71. Even though they still only received one page, it was a start. Jimmie Samuel remembers how “there was always tension when you [were talking] about the environment on campus” because the student side of things was very conservative. However it was not just the Black Student Alliance that was not being placed in the yearbook. Unsurprisingly, even the intramural involvement of black students was omitted. Even intramural sports were segregated until several black and white students put together an integrated team they called the Panthers. The Panthers became notorious across campus as they began to dominate many of the intramural sports. They even gave the law school and several fraternities quite a challenge, actually winning several intramural championships over the years. Yet the only reason any of these things happened is because of the hard work of some of the first black students at Mercer.

Even though Mercer voluntarily integrated, that did not mean that the campus provided an open or welcoming reception to the black students that were admitted. Race relations were very tense at Mercer for quite awhile, and unfortunately, not much was done by the University to lessen that tension. The administration expected the students to adapt to their new surroundings by themselves, despite the fact that many of the students were from the South, where race relations were everything, except good. However, many of the black students and white students that Mercer chose to enroll were strong, and strove to make race relations better. Part of the reason they may have been able to deal with that tension could have been their relationships with one another, and the establishment of the Black Student Alliance, an organization which enabled the black students to organize, unite and challenge the institution in productive ways.

Even though Mercer voluntarily integrated, that did not mean that the campus provided an open or welcoming reception to the black students that were admitted. Race relations were very tense at Mercer for quite awhile, and unfortunately, not much was done by the University to lessen that tension. The administration expected the students to adapt to their new surroundings by themselves, despite the fact that many of the students were from the South, where race relations were everything, except good. However, many of the black students and white students that Mercer chose to enroll were strong, and strove to make race relations better. Part of the reason they may have been able to deal with that tension could have been their relationships with one another, and the establishment of the Black Student Alliance, an organization which enabled the black students to organize, unite and challenge the institution in productive ways.

The Black Students’ Alliance: Challenging the Institution

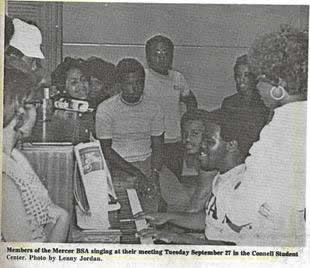

On April 1, 1969, fifty-five black students started the Black Students Alliance at Mercer University. The Alliance was open to any fulltime Mercer University student that pledged support to the principles of the organization. “This organization is based on the underlying principles of unity, self determination, collective work, cooperative purpose, creativity, and faith” (Dawson). As stated in the Alliance’s constitution, the purpose of the organization was to maintain the Black identity on Mercer Campus by creating a self-conscious Black Community promoting knowledge of Black culture and heritage, and serving as a forum for the expression of Black ideas and goals” (BSA Constitution).

Around this time, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X were setting the framework for the battle against prejudices. Jimmie Samuel, the second president of the BSA, stated that, “They didn’t really want Malcolm. I don’t think they wanted Dr. King either, but they’d rather have Dr. King than Malcolm” (Jimmie Samuel Interview). Mr. Samuel saw similar organizations from other schools using Malcolm X’s tactics and pushing change by fear. He felt that instilling fear in people was counterproductive (Oral history, Jimmie Samuel) and it only made things more difficult. Dr. Martin Luther King’s approach of non-violent protest seemed to be the best way to get the administration’s attention. Jimmie Samuel stated that, “If you go back in the archives, you’ll see on the cover of Newsweek, brothers with big afros – I did have an afro – brandishing weapons and things. They brought the authorities in. We said that wasn’t the way to go. You can’t win that battle” (Oral History, Jimmie Samuel). Jimmie Samuel explained in this interview that Black students stayed in the Connell Student Center and would not allow it to close one night. “We took Connell Student Center over one time. We grilled one of the vice presidents. He’ll never forget that. He never forgot that” (Oral History, Jimmie Samuel). They knew that change required actions that provoked critical thought rather than criticism. Even if you did something controversial, if it was done right, it could have positive results.

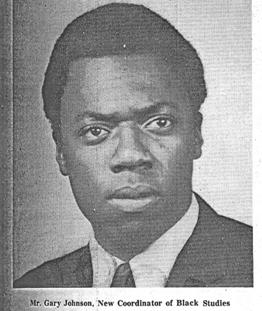

Another way that the BSA challenged the institution was by simply writing down its beliefs and goals. In a founding document, the Black Student Alliance lays out several positions on issues that they wanted to be addressed by the University. They are “Black student enrollment, Black Studies, Black faculty, Black administrative personnel, Black cultural center and campus recreation, and Mercer’s relationship to the Black community that surrounds it” (BSA Founding Document). At that time African-Americans made up 12% of the United States population and 30% of Georgia’s population (BSA Founding Document). Increasing African-American enrollment leads to the Alliance’s stance on Black studies. This document also asserted that the current curriculum, which did not include Black studies, put all students at a disadvantage as they entered the real world because the BSA believed that, “Mercer should be a servant to the society in which it sends its graduates” (BSA Founding document) and that by not having black studies in a society were blacks had a significant presence, Mercer was not serving society sufficiently. “Since Mercer does have Black students, it is necessary to have individuals in the administration that are cognizant of problems of Blacks and will make administrative judgments with their interests in mind” (BSA Founding Document). The Alliance also saw that the number of Black professors was not equal to the ratio between Black and White students on Mercer’s campus. This document also states that Mercer’s failure to hire Black professors is “a refusal to adequately integrate the educational processes here” (BSA Founding Document). Black professors are vital to the education of the student body because, as the Alliance stated, black students currently had no one they could accurately relate to. Their push for black faculty and black studies eventually led to Gary Johnson, a Mercer alumnus, to be hired as the coordinator for the black studies program (which also took serious effort to get started).

The Black Students’ Alliance also wanted to get Mercer more involved in the Macon community. The BSA asserted, “Mercer seems to pride itself in the recognition of its isolation from the total Macon community and the basically poverty-stricken, mostly Black, community surrounding its perimeter. The Alliance does not support this type of isolationism and urges the University to take an active part in rebuilding the community both social and materially. Mercer must relate to the community and its problems if faith in the university is to be restored” (BSA Founding Document). The BSA felt Mercer had an obligation to its students and to the community as a whole. One way the Alliance thought to interact with the community was to implement a pre-school program. This program was “very much need in the black community and the birth of such a program in a neighboring community, Tindall Heights was the responsibility and duty of the Black students on campus” (Henderson). The Black Students’ Alliance also proposed the founding of a Black cultural center. The cultural center would be “run, managed, and maintained by the Mercer Black community” (BSA Founding Document). The center would keep books, news releases, show films, and provide a gathering place for dialogue on the problems concerning the Black identity struggle. The Black Students’ Alliance also produced and distributed a bi-weekly literary magazine titled “Spark.” Issues that are printed in the magazine reflect personal opinions of individuals and opinions from around the country on the Black struggle. (Jordan)

The BSA is an example of what can happen when students unify and think and act critically. The Black student alliance made a serious effort to eliminate disparities between black students and white students. Moreover, it played a huge role in getting Mercer to start a Black studies program and eventually hire its first black faculty member.

Getting Black Studies Started: Hard times at Mercer University

In 1969, a journal entry entitled “A Challenge to White, Southern Universities-An Argument for Including Negro History in the Curriculum” was written by Patrick J. Gilpin and O. Kendall White, Jr. These two faculty members of Vanderbilt University emphasized the tremendous need for African American Studies in predominantly white Southern universities. Gilpin and White felt that the lack of courses, studies, and programs based on the history of African Americans, would essentially misrepresent their role in the history of America. Their entry reflects the fact that, although undergraduate United States history courses were required, the history of a Negro was never factored into the equation. The history of African Americans was relentlessly disregarded by the white Southern universities, and Gilpin and White used their journal entry to encourage those schools to embrace black culture as apart of American culture (Gilpin and White 446).

Dr. Rufus Harris, President of Mercer from 1960 to 1979, witnessed many changes on Mercer’s campus. Similar to the thoughts of Vanderbilt faculty, Gilpin and White, black students at Mercer also had strong feelings in regard to starting a Black Studies curriculum. The January 20, 1970 edition of The Mercer Cluster reports President Harris discussing a Black studies curriculum with the Black Students’ Alliance. He was asked if a committee could be created in order to “begin to research the feasibility of implementing integral Black Studies into the present curriculum” (Mercer Cluster). This issue was very hot because there were opponents and proponents on both sides of it. President Harris agreed to support the development of a Black Studies curriculum provided that it efficiently taught about black contributions towards history. The Black Students’ Alliance organized African American students and decided to have a peaceful sit-in by lining the staircase all the way into the stairwell of the faculty meeting room to display their passion and support for a Black studies program. The following week in the January 27, 1970 issue of The Mercer Cluster, the Black studies debate made news once again. The Black Students’ Alliance, led by Jimmie Samuel, presented a petition to Mercer’s faculty; 102 out of 105 black Mercer students signed the petition endorsing the proposal of the Black studies curriculum. By doing this, the Black Students’ Alliance demonstrated how important this issue was to Black Mercer students.

On February 3, 1970 an issue of The Mercer Cluster declared that, “In keeping with its role as a leading southern college, Mercer has instituted a major in Black Studies” (The Mercer Cluster). Coincidently, a year after the expressive journal entry of Gilpin and White was written, the Black Studies curriculum was developed at Mercer. This long awaited field of study consisted of courses such as: The American Black Experience, Civil Rights and the Black American, Manifestations of Prejudice, and Christian Social Ethics (Mercer Cluster). The courses spanned anywhere from the Civil Rights Movement to the beginning of black history. The professors recruited to teach Mercer’s introduction to Black Studies course were Drs. Terry Todd and Richard Moore. Previously, Dr. Todd spent quite a bit of time working with the Black Studies program at Harvard University. Although Dr. Terry Todd’s teaching method was impeccable, the African American students felt that he should not teach in the Black Studies program because he was white. They believed that “No white person is capable of teaching anything about prejudice” (Campbell 197). Despite their hesitation and dismay, statistics showed that 28 out of 42 students in Todd and Moore’s introduction to Black Studies class were African Americans. In other words, African Americans made up two-thirds of the class.

Eventually, the Black students’ wish was fulfilled when Mr. Gary Johnson, a Mercer alumnus was appointed as coordinator of the program in 1972. He was the first black faculty member to work at Mercer. Even Johnson had felt the tense race relationships while he was a student at Mercer with his position as editor of the Cluster. Johnson says he tried out for the position as a junior, but he feels that he was defeated because “of his attitudes and his race” although he believes that he was elected senior year “not because of a change in his attitudes but because he became quieter in voicing them” (Mercer Cluster).

But before Johnson came in 1972, a man by the name of Wade wrote an article in The Mercer Cluster concerning the enrollment statistics in Todd and Moore’s intro to Black studies class. He titled his piece “Black Studies Can Only Perpetuate Segregation.” Wade asserted that he was quite disappointed at the university’s decision to offer Black Studies as a major. Quite bluntly he expressed, “They have defeated the actual purpose of a Black Studies program” (Mercer Cluster). Wade’s theory on the topic of the Black Studies curriculum was that it was nearly impossible for the studies to exhibit proper integration between black and white students. He felt that the goal of the studies was to educate white people about black history, but by separating the courses in Black Studies from the standard curriculum, only blacks would participate in the classes. Based on the ethnicity of those enrolled in Todd and Moore’s introduction to Black Studies class, Wade’s suggestion seemed to be somewhat plausible. In his own words he expressed, “Black Studies will have no effect until it is integrated into our present standing curriculum” (Mercer Cluster). Rather than rendering a positive outcome, Wade felt that Mercer’s separate course approach to Black Studies would only further segregate the student body.

Wade’s counterpoint raises some interesting questions. Are the histories of White America and Black America separate entities or should they be written in one master narrative? Does separating the history enlighten white students? The University can offer Black studies, but students still decide what classes they will take. If the courses are filled with Black students, then fundamentally, no change is really occurring. If this is true, how can the University actually stop segregation and improve race relations? There are no clear or absolute answers to these questions, but Mercer has been attempting to answer them.

Mercer in Modern Times: What’s Happening Now?

Today, Mercer is a diverse university. The student population and the faculty have changed radically since the ‘60’s. Black student enrollment has increased to roughly 25% in 2009, from about 7% in 1968 and 0% in 1962. Furthermore, minority organizations and groups have a significant presence on campus. So, it could be said that Mercer has “successfully integrated.” However, before a 21-gun salute is fired, the words of Mac Bryan must be noted. “Are you going to admit that integration is a failure? Not just at Mercer but throughout the land? I see it. As do you. Blacks gathering at one place on campus, whites at another. In the cafeteria, at social events, concert hall, athletic events. Black fraternities and sororities, white fraternities and sororities. How many white students attend Black History Mont h Functions? Or enroll in black studies? There is no such thing as closure. Without genuine repentance on the part of the offending party there can be no real reconciliation. Where are the evidences of repentance at Mercer or in Macon?” (Silver 129). This may be appear to be the trenchant rambling of a radical geezer, but it is filled with truth. Mercer has failed to integrate. Like Mac Bryan said, where there are students, there is self-segregation. Of course, students ultimately decide who they want to befriend are and what events they attend. Nevertheless, Mercer still has an obligation to influence those decisions.

The Black Student Alliance was created to empower and unify black students because they were significantly marginalized during that time period. Its modern incarnation, the Organization of Black Students has similar ambitions, such as “acting as a liaison among African-American students, faculty, administration, and other campus organizations,” but it does not really meet them. Even the title, “Organization of Black Students” is inherently exclusionary. Why not give it a name that is inclusive to all students? In any case, OBS allows non-Black students to join and participate, but how many non-Black students are willing to join an organization that seemingly fails to embody any of their interests? It may seem equivalent to “Black Student Alliance,” but there is an important difference. Current Black Mercer students are not marginalized! OBS has taken principles that were applicable in the social landscape of the ‘70’s and attempted to apply them to the current social landscape, thereby perpetuating what the BSA sought to eliminate. However, OBS is not the only such organization.

Likewise, the Minority Mentor program also stagnates progress. Students in the program go on a retreat before the beginning of their freshman semester. During this retreat, they meet and bond with other minority students and choose an older minority student to mentor them throughout the school year. Fundamentally, this is wonderful, but practically, it is counter-productive. Because the students already have friends from the retreat, they are less likely to make [non-minority] friends during freshman orientation. Consequently, a community consisting of minority students is formed. Now of course, the black community does not exist solely because of the Minority Mentor program. Many minority students do not even participate in it. However, once this smaller community is formed, the students just matriculate into the larger minority community, helping to preserve the dichotomy.

Today, race relations are generally pretty good. But what does that even mean? Does saying that race relations are good mean that black students and white students are able to cooperate without conflict, or does it mean that Mercer students are able to transcend racial, social, economical, and educational differences in backgrounds and enjoy their college experience together as one student body? Some might believe that the latter is the best definition and that Mercer is a good representation of that. Although it is quite unfortunate, in actuality, Mercer’s race relations fall into the definition of the former.

At the least, the racial division is definitely perceptible, if not tangible. In the student center, organizations set up tables and talk with incoming and outgoing students. Typically, these organizations stop students that are the same race as their members. Upon proceeding into the cafeteria, the division becomes even more apparent. Not just tables, but entire sections of the cafeteria are occupied by one race. Even events and parties are segregated. Facebook is the usual way that students receive party invitations. Black fraternities and sororities send invitations to black students. White fraternities and sororities send invitations to white students. Parties are usually evaluated by how many people attended and the music that was played. Club music is generally the same, so is it not counter-productive to only invite a certain population when high attendance is a goal? None of these things are surprising though. Mac Bryan spoke about all of them. Is Mac Bryan some type of clairvoyant sage? No. Unfortunately, the failure of integration is nothing new.

Integration is much more than forcing students of different races to attend the same school. It entails acceptance, understanding, and above all, unification. Mercer has accepted Black students and destabilized the tension between Black students and White students. As evidenced by the student response to the vandalism that occurred in the School of Engineering earlier in 2009 and the formation of the Black Student’s Alliance, Mercer students are fully aware of the importance of maintaining and improving race relations. However, awareness must be accompanied by action. As long as Mercer is divided into distinct communities rather than one unified community, things need to change. Nevertheless, Mercer’s progress should not be undermined by the current status of race relations. When a former member of the Black Student Alliance can say, “They [race relations] are better than when I was a student here,” progress has been made. However, no guns should be fired, no fireworks should be launched, and no corks should be popped until that progress becomes success.

Works Cited

“A Brief History.” 40th Anniversary of UGA’s Desegregation. 9 Jan. 2001. University of Georgia. 1 May 2009. <http://www.uga.edu>.

Hatfield, Edward A. “Desegregation of Higher Education.” History & Archaeology. 2008. The New Georgia Encyclopedia. 1 May 2009. <http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org>.

Henderson, George. "BSA sponsors Kindergarten." Mercer Cluster 7 Feb. 1971: Vol. 53.

Jordan, Howard. "Black Student Alliance holds second meeting." Mercer Cluster 20 Oct.1970: Vol. 52.

Dawson, Jasmine. "Black Students Organize Alliance."Mercer Cluster 29 Apr. 1969: Vol. 50.

Samuel, Jimmie, former Mercer student. Oral History. 20 Apr. 2009.

Hobbs, Joe. “Blacks Face Search For Concealed Identity.” Mercer Cluster. 9 May 1969: 5.

Cozzens, Lisa. “Brown v. Board of Education.” African American History. 25 May 1988. 1 May 2009 <http://www.watson.org>.

Gilpin, Patrick J. and O. Kendrall White, Jr. “A Challenge to White, Southern Universities-An Argument for Including Negro History in the Curriculum. Journal of Negro Education 38.4 (1969): 443-446. Tarver Library, Macon, GA. 2 May 2009. <http.//search.ebscohost.com>.

Campbell, Will D. The Stem of Jesse: The Costs of Community at a 1960s Southern School. Macon, GA: Mercer UP, 2005.

Mays, Willie, et al. “An Appeal for Human Rights.” Documents of the Civil Rights Movement. 9 March, 1960. <http://crmvet.org>.

Black Students’ Alliance Founding Document

“Black Studies Being Considered.” The Mercer Cluster 20 Jan. 1970: Vol. 51.

“Faculty Endorses Black Studies Major.” The Mercer Cluster 27 Jan. 1970: Vol. 51.

“Black Studies Can Only Perpetuate Segregation.” The Mercer Cluster 3 Feb. 1970: Vol. 51.

“Black Studies Curriculum Set.” The Mercer Cluster 13 Oct. 1970: Vol. 52.

Silver, Andrew. Combustible Burn. Macon, Ga. Mercer UP, 2002.