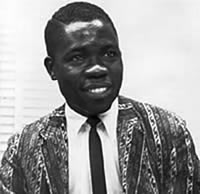

The Story of Sam Oni

by Sean Kennedy, Alden Moore, and Megan Rutherford

The story of Sam Jerry Oni is one not just one of courage but also of patience and integrity. As an African missionary convert from Ghana, he may have seemed to be an unlikely crusader for integration, but he helped Mercer challenge racist southern traditions and to find its institutional conscience.

Harris Mobley, a Mercer alumnus on mission in Africa, encouraged Oni to apply to Mercer and other universities in the U.S. Although Oni’s qualifications exceeded the requirements for most of the colleges, he received letters of denial. Mercer University was the only school to not immediately reject Oni. Had it not been for the efforts of the Mercer President Rufus Harris, his application never would have gotten a second glance. Harris assigned a special committee to deliberate Oni‘s acceptance and the general integration of Mercer. “It took over a year for the special committee that was chosen to consider racial integration to decide to give Sam Oni acceptance into Mercer” (Law 7).

Sam Oni began his experience at Mercer University in September of  1963.The first day at Mercer for Sam Oni was not the regular for most college integrations. He was not met with a giant group of violent protestors or armed guards. Instead he walked along the campus towards his dorm room, only to be met with indifferent or displeasing stares. Throughout his time at Mercer, these stares never ceased. Although Oni was involved on campus in student organizations, such as writing for The Cluster, he was still not accepted among his fellow students. He was terribly lonely and homesick. Despite these obstacles, he had a giant effect on Mercer and the very community that did not accept him. Oni certainly experienced more at Mercer than the typical college student.

1963.The first day at Mercer for Sam Oni was not the regular for most college integrations. He was not met with a giant group of violent protestors or armed guards. Instead he walked along the campus towards his dorm room, only to be met with indifferent or displeasing stares. Throughout his time at Mercer, these stares never ceased. Although Oni was involved on campus in student organizations, such as writing for The Cluster, he was still not accepted among his fellow students. He was terribly lonely and homesick. Despite these obstacles, he had a giant effect on Mercer and the very community that did not accept him. Oni certainly experienced more at Mercer than the typical college student.

Breaking Mercer University’s color barrier was not the biggest headline Sam made while in Macon. He heard of a preacher, Thomas J. Holmes being fired because he preached for racial integration. The very church that removed Holmes was on Mercer’s campus. In 1966, Oni tried to enter the Tattnall Square Baptist Church and was blocked by deacons who wouldn’t allow him entry to worship. After refusing to leave, the police were called, and they escorted Oni off of the property. While charges were not pressed, Oni was encouraged to not return. Sam could not believe that the same people who converted him to their religion would bar him from their place of worship. Therefore, he decided to prove another point by ignoring the warning he received. Again, Sam went to the steps of Tattnall and again he was met with the same discriminating faces and told to leave. Instead, Oni preached a brief sermon in front of the news cameras that had filmed the entire event and peacefully and willingly left (Patterson 16).

After this “faith-shattering experience,” Oni graduated from Mercer with a degree in sociology, and he vowed never to return to Georgia. He then went on to graduate school at the University of California to study journalism. After graduating from Berkeley with his masters in journalism, Oni returned to Nigeria. He started Project Ploughshare, the non-government organization focusing on rural development (Ellerton 1). Oni was invited back to Mercer in 1994 for the thirtieth anniversary of desegregation. Oni broke his vow of never stepping on Georgian soil ever again to speak at this anniversary. He received standing ovations and was overjoyed with the response Mercer had towards his arrival this time. Since then, he has reconciled with Mercer and has become one of the University’s strongest supporters.

Sam Oni is living proof that the smallest actions from one person can make the greatest difference. Sam could have stayed in Ghana and never witnessed the unfortunate events happening in America during his college career. He could have ventured through Mercer bowing down to the beliefs he did not agree with. Instead, Sam Oni took a giant, courageous step towards equality. He certainly challenged the city of Macon and the campus of Mercer, but he admits that, “he would do nothing differently.”

Sam Oni’s contribution to Mercer will never be forgotten. His portrait now hangs in the Lee Alumni House and a scholarship is set up in his name that brings one African student to the school per year. Oni’s story again is undoubtedly one of courage, but without the patience and integrity ideals he continuously upholds, his story would not have been the same. In the words of Rufus Harris, “This was Mercer’s finest hour.”

Works Cited

Law, Medrika. “Sam Oni.” Bear Tracks. 12 April 1999: 7.

Patterson, Tricia. Sam Jerry Oni: The Diary of a Black Man Confronting Segregation in Churches.” Baptists Today. 6 March 1997: 16.

Ellerton, Delbert. “Mercer’s First Black Student Returning to Honors.” The Macon Telegraph. 11 January 1994: 1A.

Sam Oni and Tattnall Square Baptist Church

Sam Oni’s acceptance of the Christian religion was the direct result of the Southern Baptist missions. Mission trips to foreign countries have always been a large part of the Baptist church and most churches take pride in their efforts to bring people to the Lord. In Ghana, where Oni called home, missionaries had been spreading Christianity to willing recipients for over 113 years. The first to arrive in Ghana was Reverend Thomas Bowen in 1830. Since 1830, Ghanaians were intently seeking to know Christ and to practice the same faith and beliefs that their missionaries did. However, as Sam Oni learned, the way in which the missionaries worshiped along with their converts in Africa was not practiced back in the homeland. In fact, the contrary occurred.

In James Sessions article, “Civil Rights and Religion” he claims that “Sunday is the most segregated day of the week.” This statement could not be truer of the Sunday morning worship in small town Macon, Georgia. African Americans and Whites worshiped in separate churches across town, never once coming together although they believed in the same God and lived by the same Christian ethics. This stratification within the Christian faith was accepted as the prevalent means of worshiping. When Sam Oni arrived in the Macon in order to attend the Baptist based Mercer he learned that he was expected to become accustom to this standard. Oni was very strong in his faith, and wanted to attend church to continue his growth in the Lord. However he found that this was a herculean task.

Tattnall Square Baptist Church was the first to bar his entrance. Before Oni even set foot on church grounds a member of Tattnall, Clifton Forrester visited Oni stating that “he didn’t think his congregation was quite ready to accept him.” In other words, Oni would not be allowed to worship among the same congregation that was converting his people in Africa. This one instance alone shows the hypocrisy that existed within the Southern Baptist faith at the time. In Russell Hilliard’s letter to the Christian Index he questions the duplicity stating, “Is it fair for me to ask: why in the world did we send a missionary to Ghana to preach the love of God if we didn’t expect God to keep his promise and save some soul?” This sort of racial dichotomy was de facto segregation at its worst because it was faith based. These were Christians “making a mockery of Christian ethics.” In the book of Mark, God dictates the commandments that followers of the Christian faith are to follow. Chapter twelve verses thirty one and thirty three God says that, “Love your neighbor as yourself. There is no commandment greater than these. To love him with all your heart, with all your understanding and with all your strength, and to love your neighbor as yourself is more important than all burnt offerings and sacrifices." However, the same churches believing in this idea, the same preachers who conveyed this message from their pulpits on Sundays denied Sam Oni into their church.

Day of Reckoning: September 25, 1966

http://crdl.usg.edu/voci/go/crdl/dvd/viewItemc/wsbn50156/flash/6505

On September 25, 1966 Sam Oni decided to enter the doors of Tattnall Square Baptist church. In deciding this Oni would be a part of something bigger than himself. He would be more than a man, he would be a prophet sent from African who would break the color barrier, and force Southern Baptists to confront the belief in the Christian faith. In his address at Mercer University in 1994 entitled, “Sojourner’s Truth,” Oni stated, “I, an African Christian, converted by Southern Baptists missionaries, provided the most compelling and unassailable argument against the continuation of racial segregation as practiced in Southern Baptist churches” The New York Herald even called him “a missionary in reverse.” As Oni attempted to walk through the “closed” doors of the church he was abruptly stopped by two ushers who would not allow him to enter. Tattnall has taken a closed door policy on allowing Negroes into the church. In an interview Oni recalls this denial as one of the most harrowing experiences of his life. On this day Oni “had come unto his own and his own received him not.” Although Oni had been the target of rejection and racially driven hate at Mercer University, that rejection was trivial in comparison to be driven away from the house of God.

On this same day in September the church received a bomb threat via telephone claiming that failure to allow Oni to enter the church would have deadly consequences. Although the threat was suppressed, the reality of what Sam represented came to the forefront. Sam was the catalyst for the day of reckoning for members of the Southern Baptist faith. A sign was placed in front of the church with the words, “Red Yellow Black or White they are precious in his sight.” Although the sign was removed before the services took place, the message radiated throughout the congregation. Equality was the Christian way. However, the call for change did not come on this Sunday. In the Macon Telegraph Oni stated that, “I didn’t expect any miracles, but the world will see what is going on- the empty mockery in that holy, holy of holies.”

The pastor of the church at the time, Reverend Thomas Holmes continued to deliver his sermon, unaware of Oni being denied entrance by two congregation members. Two weeks prior to this, the congregation had made a temporary policy allowing for Negro members to attend services. However, once Sam Oni attempted to enter the church, Holmes was forced to put the issue of integrating the church to a vote. With a staggering vote of 286 to 109, the church chose to keep their doors closed, and remain segregated. Holmes, believing this to be completely unchristian, continued to preach on integration, and subsequently was fired, along with his assistant Pastor Douglas Johnson, and music director Jack W. Jones.

One black man tried to enter Tattnall Square Baptist Church. One Christian tried to reach out to his fellow Christians, and one man was denied worship based on his race.

Citations

Sessions, James. “Civil Rights and Religion.” Encyclopedia of Southern Culture. 1st ed.William Ferris and Charles Reagan Wilson, eds. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1989. 1282-1283.

“Sam Jerry Oni: The Diary of a Black Man Confronting Segregation in Churches.” Baptists Today. 6 March 1966.

Patterson, Tricia. Christian Index. 27 January 1994.

“Bomb Threat Forces Evacuation of Church.” Macon Telegraph.

“Separate Ghana Student from Integration Issue.” Editorial. The Christian Index. 21 February 1963: 6

Oni, Sam. “Sojourner’s Truth.” Unpublished Manuscript.

The King James Bible. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1998. Mark 12.31-33.