Ballard-Hudson High School

By Nikki Atkinson, Gerald Butler, Nate Link, Bobbie Padgett, Haley Roney, and Betsy Trotter

Oral history with Dr. Tommy Duval

“Almost as soon as they were emancipated, freedmen in the South began to establish schools wherever buildings and teachers could be secured” (Brown 2). The majority of original freedmen schools created in the South have little or no historical evidence of their existence. Even finding the history of black schools established in the middle 1900s is impossible to unveil in some cases. America took a huge step forward when the Supreme Court ruled in favor of integrating school systems—conclusion to the Brown vs. Board of Education case in 1954. As a result of the Brown case, many black schools were shut down and no longer used for educational purposes. The closing of Macon’s finest secondary school Ballard-Hudson High was an event that was not well documented. One reason for its lack of documentation is that the white people responsible for tearing down Ballard–Hudson knew it was a slap in the face to the black Maconites. Whites were also known to disregard or hinder the advancement of African-Americans in the South.

After Emancipation, lack of education was—and still is—the biggest hindrance for free African-Americans. Who would educate black men and women since whites wanted to keep blacks as inferior as possible? One answer was the American Missionary Association. The AMA was an abolitionist organization founded by congressional ministers. They paved the path to black education throughout many cities in the South including Macon.

In 1865, the first freedmen schools were established in Macon. The Western Freedman’s Aid Commission and the Freedman’s Bureau dually created these four schools and named them the Lincoln Free Schools. Each school was located in the basement of an African-American church and staffed by local teachers, two of which were white. Some teachers were ex-slaves who taught with what little education they had. Although the education was inadequate when compared to the white schools, attending one of the Lincoln Free Schools was quite an achievement in the eyes of African-American Maconites. The overall enrollment in Macon’s freedmen schools was consistently held at approximately 600 students within the first few months, an astonishing rate.

Shortly after the Lincoln Free Schools were opened and running smoothly, the Western Freedman’s Aid Commission and the Freedman’s Bureau passed on their responsibility of the schools to the American Missionary Association. The AMA now had control over black education in every major city in Georgia. Unfortunately, the African-Americans that were teaching at these freedmen schools were replaced or reassigned as assistants once the AMA took over. On one hand, the pupils were receiving a higher education, but on the other hand, black Maconites were losing jobs.

The Freedmen’s Bureau opened a new school for blacks in Macon. The school was named after General John R. Lewis—director of the Freedman’s Bureau in Georgia. In March 1868, Lewis High School was opened for grades seven through twelve and was one of the first secondary schools for blacks in Georgia. The facility was built in a “sightly lot” on Anthony Street a few miles outside down town Macon. This would be the first school actually located in its own building. The local African-American community welcomed Lewis High with open arms, and it was nicknamed Macon’s “Home” by African-Americans. The AMA intended to use Lewis High as a school that would provide model training for teachers in the South. The opening enrollment started with 809 total pupils. Lewis High was the only school in Macon to offer normal training to its students, and Lewis easily set the standard for teacher training through normal instruction.

Other private black schools and charity schools opened relatively near Lewis High. These independent schools caused a drop in Lewis High’s enrollment. Although the tuition of attending Lewis High was fifty or twenty-five cents per month, some black children were sent to other schools with tuition at one dollar per month. One reason being that colored teachers taught them there. “Despite a growing number of these satellite schools that siphoned off potential students, Lewis High remained the choice of schools for blacks in Macon, as it was the only one that provided secondary and normal training” (Brown 45).

On July 7, 1875, Lewis High School suffered minor damage due to a fire. “The beams and flooring between the schoolhouse and chapel were well saturated with coal oil, and a black man seen loitering about the area had been under the chapel” (Brown 65). Black as well as white citizens rushed to fight the fire. The new school year started shortly after the fire broke out and abruptly came to an end. Lewis High was set on fire once again. On the night of December 13, 1876, the school was completely destroyed by arson. The Macon Telegraph reported that firemen were slow to arrive but worked hard in an effort to extinguish the flames. It was also reported that the fire was accidental. The John A. Rockwell home served as Lewis High School’s teaching facilities until the school was rebuilt.

The school reopened on March 24, 1878. A new two-story brick building was built as Lewis High’s new facility. This building was smaller than the original and served dually as both a school and a Congregational Church. The classrooms were crowded and the facility as a whole was inadequate for their present needs. The enrollment coming in to the new high school’s first year held at 93 students, and enrollment fluctuated over the next few years. Factors such as expense of tuition, change in principals, pupils working to raise money in order to attend the next school term all played a part in the change in enrollment. Despite the factors leading students to drop out and reenter, Lewis High was the only school in Central Georgia teaching secondary school. Thus, the overall enrollment rates increased dramatically over only a few years.

Industrial education became a popular trend for schools in the South. These programs taught wood working (primarily carpentry), the use of tools, repairs for facilities and furniture, and general construction. John Slater was responsible for the big push in industrial education. He started a financial aid program called the Slater Fund Board. Slater’s program was “devoted to teacher training along industrial lines.” In order to receive money from the Slater Foundation, schools must agree to have a new industrial shop added to their building where the industrial arts classed would be held. “In 1883, a two-room wooden annex was added to Lewis school…In that year the Slater Fund again gave $200 to Lewis School, and the following year Slater funding more than doubled to $500” (Brown 80). Lewis High School underwent a name change to Lewis Normal Institute due to the great deal of funding from the Slater Fund. The new name reflected the school’s dual components—teacher training and industrial education.

The Lewis School underwent many changes that eventually led to it becoming the Ballard-Normal High School. Stephen Ballard, a prominent supporter of the AMA who helped fund struggling schools around the South, appropriated funding to Lewis Normal. He visited Lewis Normal in 1888 and decided then that its physical plant needed to be improved, so he donated funding for a new, eight-room, brick building that could house up to six hundred students. In total, his donations amounted to over twelve thousand dollars. Ballard’s sister also helped Lewis Normal’s progress. She donated nearly seventy-five hundred dollars, which lead to the construction of a new girls dormitory. The dorm was named Andover Hall after the Ballard’s hometown in Andover, Massachusetts.

After these generous donations, AMA secretary Beard officially announced the change from Lewis Normal Institute to Ballard Normal School. To compete with other outside donations, Slater Foundation increased its funding to Ballard Normal from five hundred dollars to eight hundred dollars in 1889. With this new increased funding from multiple sources, Ballard Normal emerged as a premier teaching school for African-Americans not only in Georgia, but also throughout the South. Attendance at Ballard Normal continued to increase, reaching an average of nearly five hundred pupils a year, even with competition from the public school system. This was the highest that attendance has been since the creation of the Georgia Public School System.

As Ballard Normal continued to progress, many felt it needed to become more intimately involved in the community of Macon. The AMA felt that the perfect way to do this was to make Ballard Normal a junior college for many African-Americans who normally would not pursue higher education after high-school. This plan was first designed in 1936, and was accepted out of a need in Central Georgia for furthering teacher training and prospective teachers without certificates. On September 8th, 1936, Ballard Normal opened its doors for a new fall term. Available records, however, show that Ballard Normal never materialized into a junior college. Information is not available as to why.

Although Ballard Normal experienced financial difficulty during the Great Depression and depended on the Macon community for contributions to continue running, by the 1940s, it became one of the most thriving institutions in the surrounding area. In 1942, the American Missionary Association released a statement that entitled Ballard Normal to disaffiliate with the AMA due to tuition fees that alienated the common, middle class student and only supported the “better-to-do group of Negroes.” Ballard Normal would lose its private status and be converted into a public cooperative high school that would educate all African American students regardless of expense.

Once Ballard Normal made the transition from a private high school to a public high school, drastic changes happened. With a newly established public title, Ballard Normal had to abide by all Georgia public school laws and regulations. One of the most disheartening changes occurred when Ballard Normal was forced to dissimulate its biracial faculty due to the law that banned the intermingling of white and African American teachers. Beloved faculty members, with the exception of the current principal James A. Colston and two other teachers, were left unemployed after that AMA withdrew nearly all of their funds and tithes to the school. However, the AMA assured the public that Colston would be able to continue to foster the progression of Ballard Normal and would persistently serve the entire schooling community to his fullest ability. Colston’s vibrant and assuring personality as well as the list of accomplishments he was able to achieve in his mere four years as principal rested the troubled minds and ill feelings of the community. The public was also able to rest assured upon that Colston would serve as intermediary between the AMA and Macon officials, thus smoothing the transition from a private to public school and faculty release.

Once Ballard Normal made the transition from a private high school to a public high school, drastic changes happened. With a newly established public title, Ballard Normal had to abide by all Georgia public school laws and regulations. One of the most disheartening changes occurred when Ballard Normal was forced to dissimulate its biracial faculty due to the law that banned the intermingling of white and African American teachers. Beloved faculty members, with the exception of the current principal James A. Colston and two other teachers, were left unemployed after that AMA withdrew nearly all of their funds and tithes to the school. However, the AMA assured the public that Colston would be able to continue to foster the progression of Ballard Normal and would persistently serve the entire schooling community to his fullest ability. Colston’s vibrant and assuring personality as well as the list of accomplishments he was able to achieve in his mere four years as principal rested the troubled minds and ill feelings of the community. The public was also able to rest assured upon that Colston would serve as intermediary between the AMA and Macon officials, thus smoothing the transition from a private to public school and faculty release.

However, the Macon community was shaken in 1943 as Colston left his duties at Ballard Normal to become the president of Bethune Cookman College in Daytona Beach, Florida. A frantic AMA quickly appointed James Page, a science teacher from the Avery Institute in South Carolina, to take the place of Colston. Although well educated, Page was unprepared for his new place in the midst of a difficult situation. Once abundant, black educators became few and far between as many left the field of teaching to pursue other endeavors. The AMA also announced that 1944 would be the last year in which they contributed money for the regular operating expenses of Ballard Normal. Page lacked the personal and persuasive skills to appease the community and assure them of the bright future for Ballard Normal as a cooperative public high school. Page worked little with the community and even more so with teachers and announced his resignation before he was forcefully let go.

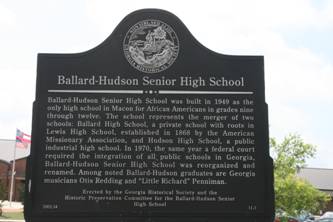

After the resignations of both Colston and Page, it seemed as though Riago J. Martin could possibly be the light at the end of the tunnel for the Bibb County schooling community and more specifically, those in attendance at Ballard Normal. As a principal for eight years in Waycross, Georgia, Martin had even more experience than his well-respected former mentor, Colston. Martin was likeable, yet effective. Dr. Tommy Duval, who was a student at the time, describes him as, “a no nonsense authority.” As the new principal for Ballard Normal, Martin headed many meetings concerning Bibb County officials’ and the AMA’s plan to establish a new high school in Macon for African American students. Plans for Ballard-Hudson Senior High School quickly became established. In this plan, Ballard Normal with its roots in Lewis High School, the AMA’s first entirely African American high school, was set to merge with Hudson High School, the city’s first black public high school. Ballard-Hudson High School was opened in 1949 as Macon’s only high school for African Americans at the time. The starting fee for the school cost an estimated $2,500,000 and provided students with the opportunity to explore three tracks that included academic, vocational, and commercial studies. Ballard-Hudson consisted of a staff of fifty-five black teachers and served approximately 1,200 students its opening day.

Ballard-Hudson High School continued to run smoothly and effectively, educating African American students for nearly twenty-one years until desegregation reached Macon, Georgia. Appointed just before the ruling of the Brown decision, Judge William Augustus Bootle of the US District Court was a key figure throughout the events leading to integration. Dr. Tommy Duval notes that Judge Bootle, “sustained the law at that time.” As a conservative, white southerner, the public did not believe Bootle would see integration through, considering his lack of help and sympathy displayed toward the African American cause. In fact, he had just previously represented a group of whites that objected the construction of African American swimming pools within their subdivisions. However, contrary to the doubts of many, he implemented the desegregation of public schools consistent with Brown v. Board of Education.

Bootle attempted to implement integration as soon as possible, but the white majority vocally and even violently discouraged him. Despite the overwhelming majority against Bootle, he persisted and took to heart the words of Spright Dowell, the president of Mercer University, who stated, “Boode, you’ve got the knowledge, you’ve got the power, you’ve got the courage. Make them do it.”

Even after the Bibb County school board’s decision to not implement integration without a specific court order, Bootle persisted and eventually mandated desegregation begin in the fall of 1964. On September 1, the board gradual plan to make the monumental shift went into effect. Although hesitant, the Macon community was asked to work in unison to “build an educational system that would serve the needs of all children.” Change was coming so slow that it was beginning to feel as if it may not come at all.

Finally, the Macon NAACP and Bootle achieved a victory for the educational community as the US Supreme Court ordered Bibb County schools to forcefully  integrate within two weeks of February 1. Bootle also ruled in favor of a freedom of choice desegregation plan that would establish a 60-40 white to black ratio and in turn abolish all black schools, such as Ballard-Hudson, to classify Bibb County schools as unitary, which was the desire of the federal courts. Although this plan was reversed by the Court of Appeals and Bootle was asked to implement a more “thoroughgoing desegregation plan” by February 16, Ballard-Hudson High School was reorganized. In 1970, African American students of Ballard-Hudson were merged with those from Willingham and McEvoy to create Southwest High School.

integrate within two weeks of February 1. Bootle also ruled in favor of a freedom of choice desegregation plan that would establish a 60-40 white to black ratio and in turn abolish all black schools, such as Ballard-Hudson, to classify Bibb County schools as unitary, which was the desire of the federal courts. Although this plan was reversed by the Court of Appeals and Bootle was asked to implement a more “thoroughgoing desegregation plan” by February 16, Ballard-Hudson High School was reorganized. In 1970, African American students of Ballard-Hudson were merged with those from Willingham and McEvoy to create Southwest High School.

"Ballard Normal School (Macon, Ga.)." Amistad Research Center. The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Web. 28 Apr. 2011. <http://www.amistadresearchcenter.org/archon/?p=creators/creator&id=95>.

"Ballard-Hudson Senior High School." Georgia Historical Society. Web. 27 Apr. 2011. <http://www.georgiahistory.com/markers/3216>.

Brown, Titus. Faithful, Firm, & True: African-American Education in the South. Macon, Georgia: Mercer UP, 2002. Print.

Castillo, Andrea. "Former Ballard-Hudson Band Teacher Scott Honored." Macon.com. 26 July 2010. Web. 27 Apr. 2011. <http://www.macon.com/2010/07/26/1207020/former-ballard-hudson-band-teacher.html>.

Duval, Thomas. “History of Ballard-Hudson Senior High.” Personal interview. 21 Apr. 2011.

Grisamore, Ed. It Can Be Done: The Billy Henderson Story. Macon, GA: Henchard Press Ltd., 2005. Print.

Manis, Andrew. Macon Black and White. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2004. Print.

Seibert, David. "Ballard-Hudson Senior High School Marker." The Historical Marker Database. 19 Nov. 2010. Web. 27 Apr. 2011. <http://www.hmdb.org/Marker.asp?Marker=38198>.

“Von Tobel Appeals For Aid For Ballard Normal School.” Macon Telegraph, 31 Jan. 1933.