Freedman’s Bureau: During Reconstruction, the task of challenging white privilege and replacing it with a new multiracial democracy in the South fell to the Freedman’s Bureau. Its official responsibility was to address two major problems: the mushrooming economic crisis after the Civil War and the “Negro Question,” or what should happen to the newly freed blacks in the nation. The Freedman Bureau’s history was the link that joined race, moral worthiness, and social policy during Reconstruction. After the Civil War, the destruction of crops, farms, and the infrastructure of the South left tens of thousands of blacks and whites landless, jobless, and homeless. As the crisis escalated, a number of new and private aid societies came up with the objective of demanding that the federal government create a more formal support system for former slaves and refugees. The proposal was backed by two distinct supporting groups: northern business and Radical Republicans. Northern businessmen were anxious to establish a free-labor society in the South so that the cotton manufacturing would become more competitive. The Radical Republicans in Congress were bitterly opposed to slavery and wanted to help secure the new black vote. Abraham Lincoln signed the bill to establish the Freedman’s Bureau into law in 1865, just six weeks before his assassination. He named Major General Howard as the Bureau’s commissioner. From the start, the Freedman’s Bureau had limitations. It was established only as a temporary division of the War Department. Its lifespan was restricted to six years. The Bureau had the enormous responsibility of providing welfare services to freed persons and white refugees. It supplied food, clothing, and fuel to the poor, aged, ill, and insane, established schools for freedmen, supplied medical services, implemented a workable system of free labor in the South through supervision of contracts between freedmen and employers, managed confiscated and abandoned lands, and finally attempted to secure equal justice before the law for blacks. The Bureau was probably most successful in the realm of education, as it established many schools and black colleges that are still around today. The Freedman’s Bureau failed the most at providing emancipated slaves the ability to become independent farmers. Land ownership was the ultimate meaning of freedom to blacks and Commissioner Howard encouraged freed blacks to purchase or rent land from white landowners in the South. However, President Johnson proved an effective impediment in Howard’s plan. Johnson had hated the Bureau from its inception. A former slaveholder and Southerner himself, Johnson was determined to keep power in the hands of Southern whites, illustrated by his famous quote: “This is a country for white men and by God, as long as I am President it shall be a government for white men” (Williams 25). Johnson legally ordered that any prospects for black ownership were cut off. Lands that had been leased to freedmen were returned to their original owners. The freedmen were relegated to the status of outsiders, hirelings, and essentially glorified slaves and white elites and workers alike were restored to privilege. From its beginning, the Freedman’s Bureau’s days were numbered. It was underfunded and understaffed. Johnson did everything in his power to undermine it, and it dissolved completely by 1872. Johnson argued that it should be opposed on grounds of “Big Government,” too much spending, and too much catering to special interests. He was a proponent of self-help, advocating that individualism was the answer to economic advantage. Essentially, he wanted blacks to pull themselves up by their own bootstraps while opposing a program designed to provide them a bootstrap. The Freedman’s Bureau was only somewhat successful in what it had been set up to do. It radically challenged assumptions about racial inequality and poverty. Most importantly, it demonstrated severe limitations in the willingness of the federal government to pursue social rights for blacks and it honed themes and ugly rhetorical arguments that built opposition to the advancement of the disadvantaged. Finally, it served as the groundwork for future efforts in helping emancipated slaves. Janelle Richardson Sources

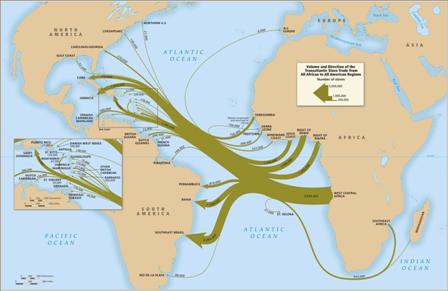

International Slave Trade: Grade-school renditions of American history suggest that most slave trade took place to benefit the American South. While a large number of slaves did disembark from slave ships on American soil, the vast majority of slave trade took place outside the US. In fact, the United States saw, at most, only ten percent of the total number of slaves taken across the Atlantic (“US Slave Trade”). Figure 1 illustrates the breakdown to slave trade origins and destinations. Two nations crucial to this practice will be investigated more fully as demonstrative case studies. Brazil The first African slaves arrived in 1538 (“Slave Routes”). While there were a number of port cities in Brazil, the ones most popular for slave trade were located on the Eastern coast in the region of Bahia. This locale offered relatively close proximately to Africa’s western coast and ample opportunity for transport further north and west into the Caribbean. Approximately 3.8 million slaves disembarked in Brazil, about 40% of the 10 million estimated Africans to have been taken across the Atlantic (Voyages). A unique by-product of the Brazilian slave trade was sovereign slave communities known as “quilombos” which consisted of escaped slaves and their families. One such community, “Quilombo dos Palmares” formed in the late 1600’s and remained free for upwards of a century. While such quilombos were usually formed by non-violent slave escapees, there were instances of slave insurrection. The Male Revolt was the most significant slave rebellion in Brazilian history. Six hundred Muslim slaves and free-men led a revolt against the Portuguese government during Ramadan of 1835. While there was relatively little bloodshed, the revolt did inspire the government to ban slave trade for fear that importing more Africans would inspire further revolts (“Slave Routes”). Hispaniola Slave trade in Hispaniola peaked in the mid 1700’s and rapidly declined after a violent slave revolt in 1791. Haitian leader Toussaint L’Ouverture, a free black man, invaded what is now known as the Dominican Republic and conducted a violent liberation of 40,000 slaves. This act of insurrection prompted many of the slave-owning elite to flee to Puerto Rico and Cuba, leaving a collapsed sugar industry in their wake. This revolt also served to frighten slave masters throughout the region for years to come. The conductors of the Male Revolt in Brazil were inspired by L’Ouverture and wore pendants of support during their revolt (“Slave Routes”). Today, much of the political, cultural and demographic landscape of Haiti and the Dominican Republic is influenced by early participation in the slave trade. Haiti’s and the Dominican Republic’s populations are 95% and 85% Black, respectively (CIA Factbook). Voodoo, a religious practice commonly associated with Haiti, is derived from a melting pot of African religions combined with Catholic liturgy. Voodoo historically served to unify fragmented people. Voodoo is still alive and well and has morphed into a supplemental religious practice for most Haitians. The final and most lasting impact of slave trade is the political divide of Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Haiti was where most French settlers set roots, while the Dominican Republic has more Spanish influences (“Slave Routes”). Kathryn Doornbos Sources:

John Brown’s Raid on Harper’s Ferry: John Brown was born in 1800 in Torrington, Connecticut. Brown was reared in northeastern Ohio’s antislavery Western Reserve, and his extremely religious family vehemently opposed to slavery. Influenced by his family and home, he developed his views of slavery accordingly. Though he was not a financially successful adult, John Brown contributed monetarily to causes in which he believed. Brown financed the publication of David Walker’s “Appeal,” a call for racial justice and action to alleviate the plight of the slaves and colored people of the United States. Henry Highland Garnet also received support from Brown for the publication of his “Call to Rebellion Speech” in which he encouraged slaves to turn against their masters. Brown also assisted in formation of the “League of Gileadites” in 1851 as a response to the Fugitive Slave Act, and its objective was to resist slave catchers and assist runaway slaves in escaping to Canada. Brown also participated in the Underground Railroad, further assisting fleeing slaves. Though he held a considerable presence in numerous abolitionist activities and publications, Brown was relatively unknown until his involvement in the 1856 massacre at Pottawotamie Creek in Kansas. The incident resulted in five deaths and was a major event in the conflict known as “Bleeding Kansas” in which the state incurred numerous losses of life over slavery. Brown continued to fight in Missouri, convinced that force was the only way in which slavery could be ended (Janney 2). He also learned methods of guerilla warfare that he would later apply in the raid on Harper’s Ferry. During this fighting, Brown began to plan for a massive slave insurrection with the hope of eradicating slavery in the United States. A group of Brown’s abolitionist supporters known as the “Secret Six,” including William Lloyd Garrison, would finance the revolt. Brown planned to raid the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia in 1858 to distribute weapons to rebelling slaves and then gradually move south, abolishing slavery in the process. Brown was forced to postpone the raid, however, because one of his men betrayed him. The postponement caused a financial setback, and his participants dwindled from approximately five hundred men to only twenty-one. Brown was not pleased with the small number of men, and yet his resolve did not alter. He proceeded to settle at a farm near Harper’s Ferry in the summer of 1859 and began to train his army in the guerilla warfare he learned while fighting in Missouri. In early 1859, Brown revealed his plan to raid Harper’s Ferry to notable abolitionist figure Frederick Douglass who advised Brown not to proceed, asserting that the raiding of a federal arsenal meant an assault on the federal government itself. Such an act of treason would have dire consequences, and Douglass informed Brown that he was “walking into a perfect steel trap” from which he could not get out alive. Douglass foresaw the consequence, but not the heroism and veneration that were assigned to Brown in response to his stand against slavery (McGlone 2). On October 16, 1859, John Brown and his men set out for the raid on Harper’s Ferry, planning to capture the weapons from the federal arsenal and escape before word reached Washington. The men worked under the assumption that local slaves would lend support and carry the insurrection movement south. The men entered the town and cut telegraph wires so no messages could be spread. They successfully captured the weapons of the arsenal and took numerous citizens of the town hostage. The raid might have succeeded, were it not for two problems that caused its failure. For an undisclosed reason, a train John Brown’s men detained for five hours was allowed to proceed to Baltimore where passengers informed authorities. President Buchanan promptly deployed marines and militia under the command of Colonel Robert E. Lee. The second issue was that no slaves came forward to revolt and join Brown’s rebellion, forcing him and his men to retreat into an engine house that came to be known as John Brown’s Fort when local townspeople and militia retaliated. When Lee arrived, Brown had already retreated inside the Fort. Lee sent Lieutenants Stuart and Greene to negotiate with Brown, and they eventually had to take the men by force. Brown sustained a serious saber wound while being captured, and he was taken to Charlestown, Virginia to receive medical care. Roughly thirty six hours after it started, the raid had ended in disaster.

This terrifying act stunned the entire nation and radicalized perceptions of abolitionism and racial equality (Faulkner 2). Some would consider him a martyr for the cause of freedom, and others, a fanatic terrorist whose mental instabilities shoved him out of control (Gallman 1-2). Whatever the case, John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry was a stepping stone directly into the Civil War that would begin only months after he was hanged. As The Richmond Enquirer accurately stated, “[the] invasion…advanced the cause of disunion more than any other event that has happened since the formation of [our] government.” Catherine Roe Sources

Further Information

The Lost Cause: In 1866, Edward Pollard wrote a Confederate history of the Civil War entitled The Lost Cause in which he claimed that, although the South must “submit fairly and truthfully to what the war has properly decide,” the southern culture would carry on its beliefs (Pollard 752). Pollard’s assertion that the South would maintain its ideas turns out to be true. The South systematically attempted to wrest moral victory out of military defeat by writing its own history of the Civil War. This revisionist history of the Civil War is known as Lost Cause ideology. Lost Cause ideology recognized that, in addition to defending its military, the South also needed to defend secession. As ex-Confederate Clement A. Evans said, if the South could not justify secession, its people would “go down in History solely as a brave, impulsive but rash people who attempted in an illegal manner to overthrow the Union” (Gallagher and Nolan 13). The Lost Cause therefore defended secession as a Constitutional right, claiming that since the states had entered the Union freely, they could leave it freely (Gallagher and Nolan 18). Additionally, the Lost Cause denied that slavery had caused the Civil War by citing various other causes, such as states’ rights, tariffs, and economic differences (Gallagher and Nolan 15). Lost Cause leaders further asserted that the South would have eventually given up slavery (Gallagher and Nolan 16). But at the same time the South claimed it would have rid itself of slavery, it also claimed that slavery provided a moral order necessary for African-Americans and that African-American virtue would plummet without slavery (Reagan 110). For example, former Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens said that the African-American male “has never been civilized until transplanted into slavery,” and Lost Cause writer Robert Lewis Dabney believed that the young African-American woman represented the sexual doom of the South (Gallagher 19 and Reagan 107). In the 1890s, Confederate organizations, such as the United Confederate Veterans (UCV) and the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), supported and contributed to Lost Cause mythology (Blight 258). The UCV held annual reunions which often featured prominent Confederate speakers who, in turn, disseminated various elements of the Lost Cause. For example, ex-Confederate J.C.C. Black, speaking at a UCV reunion in Augusta, restated the Lost Cause talking point that slavery had not caused the Civil War: “We did not fight to perpetuate African slavery, but we fought for…the God-given right of the freedom of the white man” (Blight 290). The UDC raised funds to erect Confederate monuments, often of General Lee, all over the South. These monuments have provided visual representations of Lost Cause ideology for decades. Lost Cause ideology continues to pervade southern culture. As evidence that the glorification of the Confederate military has been thoroughly effected, Gary W. Gallagher cites the preference of art patrons for Confederate-oriented art. Art advertisements featuring Confederate subjects since 1990 outnumber Union subjects 2.5 to 1 (Gallagher 138). Additionally, organizations like the United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Sons of the Confederacy continue to thrive in the South, along with the monuments their early leaders left behind. Jaclyn Crumbley Sources

Further Information

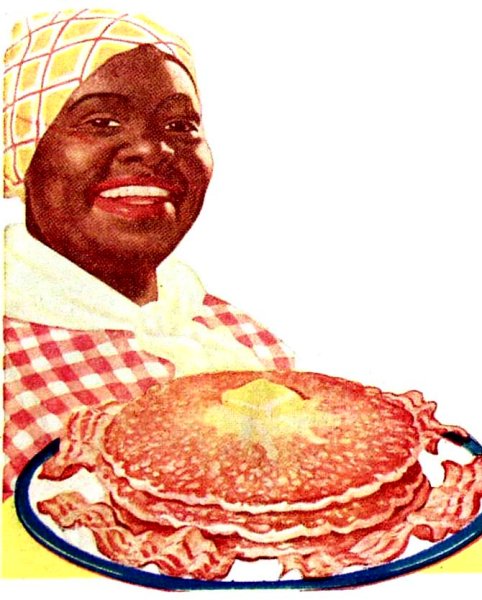

Mammy: A Century of Race Gender and Southern Memory by Kimberly Wallace-Sanders: Mammy: A Century of Race, Gender, and Southern Memory, examines the reoccurring image of the stereotyped loyal, maternal, black woman in visual and literary culture. A complex signifier of racism, sexism, and Southern nostalgia, Mammy is identified most notably by her physical characteristics: an exaggeratedly round body, dark round face, big warm smile, and an aura of motherliness. While the Mammy stereotype has been perpetuated in nearly every medium available, Dr. Wallace-Sanders argues that the Mammy figure can also be explored through her behavioral characteristics, some of which include her rich soothing voice, raucous laughter, self-deprecating wit, acceptance of racial inferiority, and marked attachment and devotion to her white charges over her own black children. Wallace-Sanders follows Mammy through three time periods from 1820’s to 1930’s and focuses on multiple mediums to “investigate the shifting, rather than static, meaning of ‘Mammy’” (Collins). Although early physical descriptions of mammy are not heterogeneous, and indeed the title “mammy” was seen in other forms such as “Negro nurse” or “baby nurse” (Wallace-Sanders 14), certain behavioral traits remain consistent. Wallace-Sanders differs from many scholars in that she places Mammy’s relationship to her own children at the center of the analysis. Subsequently, an important note is that early Southern literature depicts the mammy figure as preferring her adopted white children to her own. This depiction is complicated in many ways, but the obvious racist insults are that “African American mothers aren’t affectionate and loving toward their own children” and that “African American children were both subhuman and dispensable, represented as being more like pets than real children” (Wallace-Sanders 26). Wallace-Sanders also examines the cultural significance of Topsy-Turvey dolls, rag dolls that joined a child with a black woman. These dolls are visual images that symbolize a cultural understanding of a black woman’s bonded relationship to white children. This relationship of overemphasized maternal care and familial love can be fully seen in the mammy character of Aunt Chloe from Uncle Tom’s Cabin. All of Aunt Chloe’s characteristics both behaviorally and physically mark the first highly popular concretization of Mammy in literature. Her image and behavior was then reproduced over and over. Even in northern and antislavery literature, the mythology was perpetuated that slaves and slaveholders existed in a mutually happy, familial setting. After the tremendous success of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, many proslavery and antislavery responses to the novel emerged. Most notably, Wallace-Sanders focuses on the early African American responses of Frederick Douglass and Harriet A. Jacobs. In his 1855 narrative, Douglass altered the portrayal of his mother to counteract representations of the mammy stereotype, and Harriet A. Jacobs undermines the mammy image by describing her painstaking efforts to care for her own children (Mitchell). Wallace-Sanders investigates Mammy in advertising and Published one year after the introduction of Aunt Jemima, Mark Twain’s Pudd’nhead Wilson plays on a combination of an ever-growing fear of miscegenation and the southern nostalgia for the faithful mammy. Although very white, Roxy possesses many of the Mammy characteristics. Twain blends stereotypes to create a tragic mulatto character who’s passing is across maternal boundaries rather than a color line (Wallace-Sanders 73). Through a twist of racial stratifications, Roxy becomes a “mammy” to her own child. Charles Chesnutt’s “Her Virginia Mammy” is another example of a complex embodiment of racial issues. The orphaned Clara recovers her biological mother but instead represses her heritage by instead accepting her mother as a black mammy. While Roxy and Mammy Jane may have more “complexity and greater depth than Aunt Jemima in popular culture,” (Wallace-Sanders 92) the image of Mammy still emanates from their characters. Moving into the 20th century, Wallace-Sanders focuses on the Lost Cause-era movement to establish monuments to the faithful slave. In an effort to justify the plantation system, the injured southern states made a political and cultural effort to “correct” history by shifting “emphasis from slave labor to slave loyalty” (Wallace-Sanders 97). Many monuments erected during this time depict African American soldiers who fought for the Confederacy to symbolize the Negro’s commitment to the Antebellum South. The United Daughters of the Confederacy often funded these monuments, along with many projects to monumentalize the “good old black mammy of the past” whose “loyal conduct refutes the assertion that the master was cruel to his slave” (Southern Spaces). The penultimate chapter compares representations of Mammy in Gone with the Wind (1936) and The Sound and the Fury (1929). According to the author, Mitchell’s Mammy, played later by Hattie McDaniel, and Faulkner’s Dilsey both represent the relationship between black women and the southern family (Collins). Through a comparison of these characters and an analysis of this dynamic, Wallace-Sanders concludes that the idea of Mammy is a common ground in which the conflicts of the “Lost Cause tradition and the special burden of Southern memory are fought within the domestic sphere of family life” (Wallace-Sanders 119). Dr. Wallace-Sander’s book gives us a fresh look at the shifting progression of the Mammy stereotype, from its early, scattered origins to a solid representation, which has remained ingrained in the American psyche. The mammy character is one that helped to spread the ideology of the Lost Cause and promote a false idea of sectional healing. Since her image is one of complex racial and sexual myths, Wallace-Sanders emphasizes the importance for exploring the different historical interpretations of Mammy to better disentangle fact from fiction. In this way Wallace-Sanders succeeds in illuminating cultural understandings of race and gender. Charles Peterson Sources

Matthew J. Mancini: One Dies, Get Another: Convict Leasing in the American South, 1866-1928 Matthew J. Mancini’s One Dies, Get Another documents the unmitigated suffering of African-American convicts in the post-Civil War American South. The book dissects the penal labor system instituted in all of the former Confederate states except Virginia. Mancini divides the book into three parts: the first analyzes the economic and political circumstances that gave rise to the practice’s formation; the second examines the character of convict leasing in each individual state; and the third discusses the events that led to its dissolution. He holds the view that convict leasing was worse than slavery, due to the brutal methods used by lessees to maximize production while spending as little as possible on maintenance. Although the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment was a major historical breakthrough in African American civil rights legislation, it has also come to be a diversion from the significant role played by convict leasing for nearly a century after emancipation (Lichtenstein 2). In the South the control of the convict population given over entirely to the contractor, as Georgia's Supreme Court explains: "Of course a leased convict is not property. He is a human being and the State owes to him the same duty that it would owe to any other human being under the same unfortunate circumstances.... His labor, however, during his term of service, is a property right that may be the basis of a valid contract" (138 Lichtenstein) Although the Republicans secured amendments and the Congressional Reconstruction Acts, white supremacist groups, the most prominent being the Ku Klux Klan, used threats to make certain that freed blacks understood the reality of disadvantages they faced (Fierce 16). Also, politicians and enforcers of the law specifically targeted African-Americans. As the dependency on convict labor grew, law and economics became intertwined. By 1870, white supremacy was no longer in question (Fierce 20). In one month, Macon, Georgia's recorder court sent 124 men and 25 women to the county chain gang for a total of 6,751 days of labor. Fifty-six of these convictions were for drunkenness, 40 for disorderly conduct, 18 for fighting, 12 for loitering, another 12 for violating city ordinances, 4 for reckless driving or riding, 2 for throwing rocks, and 1 simply for being "suspect" (Lichtenstein 169). By 1908, Georgia’s black convicts outnumbered the white prisoners nearly ten to one (Lichtenstein 15).

The prisons' attitude toward the cruelties inflicted on convicts by lessees can be summed up with one prison lessee's response to George Washington Cable's address on convict leasing to the 1883 National Prison Association: "Before the war, we owned the negroes. If a man had a good negro, he could afford to keep him...but these convicts, we don't own 'em. One dies, get another" (Mancini 3).

In its report, a legislative subcommittee recorded an account of convict torture: "A half-starved convict is thrown upon his back, and while in that condition, a machine attached to a hose is thrown over his nose, and water is thrown into his nostrils until he is almost strangled, and as that victim shows signs of reviving, the water is turned on and the strangling process is repeated until the victim has barely life enough left in him to rise from the ground" (Fierce 155). Defenders supported the radical ideology of Redemption, which argued that the prisoners were corrupt and should not be released back into society, while the free blacks must be reformed. Former Georgia Governor John Brown explained, "those who were trained as slaves shall have died, leaving only a race of depraved vagabonds." However, even Brown could not deny that the "justice" of Georgia's penal system was questionable. By admitting that "casualties would have been fewer if the colored convicts were property, having value to preserve," he supports Mancini's belief that the convict system was worse than slavery (59 Lichtenstein). Some defenses were focused on support of the social distinction of black and white prisoners. As Reverend H. H. Tucker, former chancellor of University of Georgia and former President of Mercer University argued, "the convicts are of two races, what is paradise to one is purgatory to the other." Tucker was one of the most proactive defenders for leasing, and his only complaint was "the great leniency of the system" (61 Lichtenstein). In July, 1908, the Georgia Prison Commission released its annual report, recommending urgent action. Within the year, convict leasing was outlawed in Georgia (153 Lichtenstein). Other states did the same, but in some cases the legislation was not enforced (13 Fierce). Mancini explains that the practice was abolished because of cost, not conscience. Political reform caused the cost of convict labor to increase, giving businesses more incentive to turn to free labor and chain gangs. Convict leasing still exists today, but is regulated to the public sector. Government justifies that the treatment of convicts is strictly regulated, and any recent instances of torture are isolated events resulting from a "perversion" of police powers, which, when brought to light, will result in the elimination of offenders from their jobs (80 Wilson). Alex Westberry Sources:

Mary Chesnut's Civil War: Mary Boykin Chesnut’s diary, more commonly known as Mary Chesnut’s Civil War or A Diary from Dixie, begins with the election of Abraham Lincoln as President in 1861 and continues through the Civil War until July 26, 1865 when Chesnut admits the Confederacy’s defeat (Woodward). Chesnut’s diary is often recognized as one of the most important southern literary works of the nineteenth century and as one of the most illuminating accounts of the Civil War home front. Mary Chesnut was born on March 31, 1823 in Stateboro, South Carolina to parents Mary Boykin and Stephen Decatur Miller. Her mother came from a family of wealthy plantation owners, and her father supported states’ rights as a prominent politician (Woodward). Mary received her schooling in Camden, staying with her Aunt and Uncle, until she was twelve (Woodward). After her father resigned from his job in the Senate in 1833, the family moved to Mississippi where her father owned three plantations and hundreds of slaves (Woodward). While in Mississippi, Mary attended Madame Talvande’s French School for Young Ladies. When Mary was fifteen years old she began to receive marriage proposals, and at the age of sixteen she accepted one from James Chesnut, Jr. The young couple married a year later. After they were married, the Chesnuts moved to Mulberry, a plantation in South Carolina, and James’ political career began to grow. In 1856 he was elected president of the state senate. The Chesnuts moved to Washington DC for James’ career, but they soon moved back home after Lincoln was elected President. James attended the first Confederate Congress in Montgomery. Mary started her diary after this move from Washington. She wrote of the fears and dreads of the war, as well as her wartime experiences. She kept a close watch on the politics and military affairs of the Confederacy and often wrote with impatience and disgust at the incompetence she witnessed (Woodward). From Mary’s account, the best of times were those spent in Richmond where “life was one extended house party and gossip-fest in cramped quarters with the domestic affairs of great and near-great under close scrutiny” (Woodward xl). Though there were these moments of fleeting happiness, Mary’s story is “predominantly one of grief, anguish, pessimism, and anxiety” (Woodward xl). Because of James Chesnut’s political career, Mary was able to provide a first-hand view of the political war of the Confederacy. She traveled with James to Montgomery, Alabama, where he was a participant in the Confederate Provisional Congress. Mary continued to follow her husband to Charleston, South Carolina, where he was “part of negotiations over the departure of Northern troops from nearby Fort Sumter” (Woodward). However, for Mary, the novelty of the war was soon replaced by horror at the “destruction of property, political confusion, poverty and hunger, and the tremendous number of wounded and dead” (Woodward). Mary often complained about her lack of power as a woman in the South, stating that she “wished she could be a man so she could be more active in the war effort” (Woodward). After the war ended, Mary’s husband, James, continued with his political career and spent much of his time away from the home, leaving his wife to tend to the home affairs alone. At the age of fifty, Mary began “the most productive period of her life,” and in the following years she wrote numerous works including the revisions of her diary (Woodward xlii). In 1885 both Mary’s husband and mother passed away, and the grief took a toll on Mary’s health. Mary Chesnut passed away at the age of sixty-three on November 22, 1886, from an unexpected angina attack (Woodward). Chesnut’s diary was not published at the time of her death, and “she entrusted her journals to Isabella Martin, a Columbia, South Carolina, schoolteacher whom Chesnut had met during the war” (Gardner 170). In 1904 Martin met a fellow southern woman, Myrta Lockett Avary, who had written and published A Virginia Girl in the Civil War. Avary convinced Martin of the profitability and marketability of Chesnut’s diary, and together they came into business with D. Appleton and Company. At the beginning of the publication, disputes broke out between Avary, Martin, and Appleton’s Francis W. Halsey regarding the introduction that the firm wanted for the book (Gardner). Throughout the publication process the three teammates ran into plenty of conflicts but, “[d]espite this wrangling between Avary and Martin and the publishing firm, A Diary from Dixie was released in 1905 to considerable popular and critical success” (Gardner 172). Literary works such as Mary Chesnut’s Civil War are important to understanding the South. They dispel many myths about antebellum southern culture, and they humanize the people of the South. Jill Isaac Sources

Further Information

Populism and Fusion Politics: The Populist Party began in the 1870’s as a reaction to economic depression. Farmers were sinking into debt because their crops were failing due to drought. Such a circumstance left them in a difficult position with no money and no crops with which to earn it. As a result, tensions with railroads, lenders, and others with which the farmers interacted came to the surface. Tensions deepened as the depression got worse. The farmers’ response to these tensions was to take action on a political level and form the Populist Party, also known as the Peoples’ Party. The name was fitting, for the Party was created to represent the interests of ordinary people who demanded reforms that were ignored by the elite who held power. The Populists were calling “for the return of government to the small producers, the ‘plain people’” (Burgin 126). Party members were most common in the Midwest and the South, areas where farming was the key economic pursuit. The Populist Party officially emerged in 1892 with a merger between the Farmer’s Alliance and the Knights of Labor. The Farmer’s Alliance formed in the 1880’s when local political action groups in the South and Midwest voiced their discontent and united to find relief through political action and change the laws that “shaped nineteenth-century public life” (John 332). The relief was necessary due not only to the drought, but also to the significant economic change after the Civil War from a plantation economy to something quite different. The Knights of Labor were formed in 1869 in Philadelphia, and their purpose was to organize the labor of the working class. This group enacted strikes and demands for higher wages among a host of other actions to alleviate their plight. They spread to Chicago in 1877 after the railroad strikes. The highlight of the actions of the Populist Party came in the 1896 presidential election. At the St. Louis Convention of the Populists, two factions developed. The fusionists advocated a merger between the Populists and the Democrats. The mid-roaders, however, did not want to unite with either the Democrats or the Republicans. Their fear was that the Democrats would squelch the Populist platform in place of their own interests, a fear that would prove well-founded. At the convention, William Jennings Bryan was nominated as the presidential candidate for both the Democratic and Populist parties. To the mid-roaders, the Populist platform was tantamount to their candidate whom they reluctantly supported. The Populist platform for the 1896 election reflected their purpose. The goals were to demand federal intervention to eradicate the depression, stop corporate abuse, and prevent poverty among the farming and working classes. But the currency debate was perhaps the most significant subject in the 1896 election, and the Populists advocated free silver as opposed to the gold standard. With free silver, inflation could be induced and crop prices raised to ease farmers out of debt. This issue of bimetallism drove the 1896 election in which the Republican candidate William McKinley defeated Bryan. Complex distinctions also existed between local and national organizations of the Populist Party. Fusion between parties would seem to denote a simple union, but the union and the interests of the parties being united brought complications. On a national level, the Populist Party fused with the Democrats. On a local level, particularly in the South, the Populists had a tendency to fuse with the Republicans. The local level consisted of the combination of poor whites and blacks joining together against Democratic control in an “interracial coalition under the Populist movement” (Gerteis 198). The Republicans and blacks were prevented from gaining power on the local level due to Democratic dominance and monetary control. Their union, however, created a majority that was able to unseat many local Democrats in 1894 elections. Chesnutt’s novel, The Marrow of Tradition, depicts the discontent of North Carolina Democrats as a result of Populism through the character of Carteret who states that “his own party, after an almost unbroken rule of twenty years, had been defeated by the so-called ‘Fusion’ ticket, a combination of Republicans and Populists” (Chesnutt 62). The depth of this discontent can be seen in the response the Democrats undertook to ensure that their power was restored. In 1898, the “White Supremacy Campaign” ended the Populist Party. Using phrases such as “Negro Rule” and “Negro Domination,” the Democrats ensured that all white allies of the blacks left their majority union due to the racial barriers exploited by the white elite. Through means such as Red Shirt intimidation, reminiscent of the Klu Klux Klan, the number of Populist and Republican voters decreased until they largely ceased to exist. The Democrats, “[b]y fraud in one place, by terrorism in another, and everywhere by the resistless moral force of the united whites” eliminated the Populist Party and pulled blacks into “the apathy of despair, their few white allies demoralized” (Chesnutt 192). Works Cited

For Further Information

Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution by Eric Foner: By its very nature, scholarship is supposed to offer a progressive viewpoint. But as historian Eric Foner asserts in his book Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, the first sixty years of Reconstruction era scholarship yielded studies that merely reinforced and helped to legitimize the dominant racial attitude of the day. Rather than offer objective study of historical fact, historians from roughly 1900 to the early 1960s largely overlooked black agency, instead preferring to uphold the popular “Lost Cause” interpretation of the past that vilified radical northerners and blacks and glamorized white southerners. Not until the emergence of the civil rights movement in the 1960s did the academic community begin to question this prevailing interpretation, and even then it took almost a decade to overturn. Foner argues that while much progress has been made in the roughly twenty years between the reversal of this interpretation and the publishing of his book in 1988, a coherent account of Reconstruction taking into account new perspectives has yet to be produced. With Reconstruction, Foner aims to provide a “broad interpretive framework” which synthesizes “the social political, and economic aspects of the period” while also keeping in mind “the findings and concerns of recent scholarship” (Foner xxiv). The scholarly study of Reconstruction began in the early 1900s with the work of William Dunning, a professor at Columbia University whose view of the period has come to be known as the Dunning School. The basic tenets of Dunning’s interpretation reinforced the Lost Cause mentality, casting Reconstruction as “an era of corruption presided over by unscrupulous ‘carpetbaggers’ from the North, unprincipled Southern white ‘scalawags,’ and ignorant freedmen” (Foner xix). But central to the narrative of the Dunning School, Foner asserts, is the belief in “negro incapacity,” or the notion that blacks “were unprepared for freedom and incapable of properly exercising the political rights Northerners had thrust upon them” (Foner xx). Despite its obviously racist underpinning, the Dunning School remained largely mainstream for the first half of the twentieth century. Some dissenting voices were cast, such as that of W.E.B. Du Bois in 1935. But for the most part, opposing viewpoints were “largely ignored” by the scholarly community (Foner xxi). Foner asserts that the fall of the Dunning School took more than a simple evolution in scholarship. Rather, it required “a profound change in the nation’s politics and racial attitudes,” one which “bore the mark of the modern civil rights movement” (Foner xxii). Only when the nation became more open to the notion of racial equality in the 1960s did scholars begin to look at Reconstruction through a more racially progressive lens, beginning what he calls the revisionist period of scholarship on the era. Under this revisionist interpretation, Reconstruction was no longer viewed as a “tragic era of rampant misgovernment” and “Negro rule,” but as a “time of extraordinary social and political progress for blacks” (Foner xxi). For the first time, mainstream academia agreed that Reconstruction represented a time of positive rather than negative radical social change. By the 1970s, however, many scholars had begun to question the optimistic outlook central to the revisionist interpretation, arguing that it painted all-too-cheery a portrait of racial progress. These “post-revisionist” scholars asserted that Reconstruction was an era neither of significant negative nor positive social change and that, in fact, it engendered little real progress toward equality whatsoever. As C. Vann Woodward observed in 1979, these post-revisionist historians pointed out “how essentially non-revolutionary and conservative Reconstruction really was” (Foner xxiii). Asserting that Reconstruction “can only be judged a failure,” Foner falls somewhere in line with the trend of post-revisionism study. Yet unlike other post-revisionist scholars, such as Michael Fitzgerald, who dubs the period a “splendid failure,” Foner does not completely discredit the positive changes and enduring accomplishments Reconstruction brought about, most notably with the development of black family, religious, and social institutions (Hogue 18). Reconstruction failed to accomplish its goal of lasting equality, but it did set the stage for future progress. As Foner asserts, “The tide of change rose and then receded, but it left behind an altered landscape” (Foner 602). Although the end result of Reconstruction was a violent period of Jim Crowism and disfranchisement, the period of Northern occupation from 1863 to 1877 was not completely in vain. For the first time in American history, a very small amount of blacks began to own land and businesses, opening the “doors of economic opportunity . . . doors which could never be completely closed” (Foner 603). Furthermore, the development of new legal rights in the nation’s Constitution “created a vehicle for future intervention in Southern affairs” and made it possible for the federal government, albeit a century later, to ensure legal equality once and for all (Foner 603). Carl Lewis Works Cited

Red Hills and Cotton by Ben Robertson: Ben Robertson was a loyal son of South Carolina who possessed the ability to appreciate the South for its “best traditions” while also acknowledging “the region’s many shortcomings” (Ford xi). Though Red Hills and Cotton is an Upcountry memory, rife with remembrances and insights into the beauty of South Carolina, it is also an honest appraisal of the state’s flaws. Lacy Ford, author of the Introduction to the Southern Classics edition of the work, notes that Robertson repeatedly denounced the “tendency of Southerners to use defeat…as an excuse for failure and inaction” (xi). Robertson muses about the South Carolina he loves while employing an analysis of the Southern mentality that was not “a comforting myth,” but “an ideology of paralysis and irresponsibility” (xi). Robertson begins describing the state of his heritage with the assertion that “[b]y the grace of God, [his] kinfolks and [he are] Carolinians” (3). He then states that he is a Carolinian before being a Southerner, and a Southerner before being a citizen of the United States. This manner of prioritizing reveals the extent of Robertson’s loyalty to South Carolina. Delving into his personal history, he relates that “the history of the United States is a personal epic, a personal saga, and in it from the beginning we have been taking our part” (19). History, for Robertson, is not something that is written down, but is instead transmitted through stories and related on a personal level. He and his family write it themselves, “all of [them] rich in ancestry and steeped in tradition and emotionally quick on the trigger” (7). The family of Ben Robertson maintains a considerable presence in his narrative. He gives details about the food at family gatherings, ranging from “red gravy in bowls and wide platters filled with thick slices of ham,” to details about custom that included a prayer such as “‘[g]ood God, look at this’” (66). The author also remembers Southern settings involving a “parlor with moonlight streaming in and mockingbirds singing at midnight” to “pines and the springhouse and coolness of the interior and clearness of the spring” (135). Robertson’s life is made visible and alive in such descriptions, further developing the concept of Southern memory from the perspective of Upcountry South Carolina. Offering such insight into his family and heritage, Robertson delineates his beliefs about Southern identity. Disavowing readers of concepts of standard Southern mythology, Robertson states that he and his family “were old Southern farmers” rather than “old Southern planters,” a “plain people, intending to be plain” (98). His identity is not rooted in stately white columns and mint juleps, but instead “in the Southern rhythm” (218). This rhythm came from being “surrounded by all sorts of restrictions,” but also in the beauty of land and the planting of cotton (218, 135). In addition to this plainness, Robertson also adds that Southerners “have no understanding at all of temperance,” given to great emotion (127). He sees this extreme as both a strength and weakness, caused by a “desperate craving…for the absolute in existence” (127). Pivotal to Robertson’s Southern identity is the presence of cotton. It established the Southern rhythm and was used as a tool to “set [Robertson] in the mold” as “a Carolinian, a Democrat and a Baptist” (221). Planting cotton allowed his character to be shaped “in the most exact and unrelenting form” (220). This powerful connection to cotton makes it understandable as “almost human,” as if it were “some member of the family…in whom they still believe” (161). Cotton was constancy during Reconstruction, a symbol and presence of faith as well as “rest and recover[y]” (265). Reconstruction and the South’s defeat in the Civil War presents the source of Robertson’s critiques of the region. Describing the aging Southerners, he delineates that “in their old age their strength was firm; they were stoic in repose” (113). Questions about the future plagued such resolute Southerners, as evidenced by the reactions of Robertson’s grandparents when his Great-Aunt Narcissa would begin her inquiries. She “would point to [the South’s] waste of life,” as well as “squandered effort [...] lost opportunities” and “poverty” (154). Robertson uses these questionings about the future to reveal what he believes to be the strength of the South, which is “an attitude […] more powerful than any circumstance” (149). Drawing upon lessons from his grandfather, Robertson propounds that Southerners “must work [their] way out,” and in doing so “contribute to the readjustment of the rest of America as well” (166). The author calls for the defeated South to take charge of circumstances and work ahead instead of remaining stoic. In order to deliver such concepts of memory, Southern identity, and a critique of the South, Robertson utilizes his family. He states that “[r]elationship is irrevocable in [his] worn and beautiful hills” (55). Family is wrapped within his ideas and beliefs, the source and maker of his character. Grandfather Bowen, Grandmother Bowen, and Great-Aunt Narcissa are all vessels for Robertson’s delivery of memory and analysis of South Carolina. The constructs he relates are enduring for those moments when “the past seem[s] to sweep forward into the present” and Southerners once again “take [their] place in the vast eternity of time” (294). Catherine Roe Robertson, Ben. Red Hills and Cotton: An Upcountry Memory. Columbia, SouthCarolina: University of South Carolina Press: 1991. For Further Information

Roll, Jordan, Roll by Eugene Genovese: Eugene Genovese, author of Roll, Jordan, Roll, is an American historian of the South and U.S Slavery. Born in New York in 1930, Genovese was a self-declared Marxist and Socialist who later converted to neo-conservatism. He brought a unique Marxist perspective to the examination of pre-Civil War slavery. Genovese contends that slaves inadvertently embraced paternalism by recognizing their slave owners as the “white protector” of the house, farm, or plantation. This is seen repeatedly in slave narratives of the time—there is often much description of how one slave owner is “better” or “more honorable” than another. Slaves signaled internal acceptance of imposed white domination through their reactions to punishment. Often slaves would willingly submit to a “conventional” wrongdoing, such as stealing apples from the garden. However, if punished arbitrarily for something they felt they didn’t do, often slaves experienced feelings of shame or “betrayal”—as if the slave owner shouldn’t have punished them because they owed each other some sort of familial loyalty. Genovese further expands on his paternalism model of master-slave relationships by explaining how paternalism allowed slaves to convert so-called “privileges” given to them by slaveholders into “rights.” He cites the usual custom that slaves got Sundays off, even before it was legalized. Having a day off was, at first, a privilege bestowed upon the slaves, but it became collectively viewed and standardized into a “right” by the slaves. Slave masters in turn would not violate such “rights” in order to perpetuate their claim that they were acting in the interest of the slaves’ welfare. This privilege-right exchange further linked slaves and masters to one another in a perverse “family” association, further fueling the paternalistic ideology. Because the slaves accepted this ideology and began using to achieve their own ends, they failed in forming a collective revolution to overthrow their oppressors. Though Genovese has been criticized for perhaps being a little too sympathetic towards Southern slaveholders and accused of romanticizing slavery in the typical moonlight-and-magnolias fashion, it is irrefutable that his work for Roll, Jordan, Roll is extensive and exhaustive. Considered to be the “the most influential synthetic work on southern slavery” (Sinha), it can only continue to provide insight on slavery in the Old South for decades to come. Janelle Richardson Sources:

Southwestern Humor: Southwestern humor originated in the 1830s, 1840s, and 1850s from the states of Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana (Grammer 370). The Southwestern humorists were educated, white Southern males who possessed extensive training in law but little training in literature. In fact, the best of the humorists—Johnson Jones Hooper, Augustus Baldwin Longstreet, John Gorman Barr, and Joseph Glover Baldwin—were all lawyers (Beard). They wrote because they were enraged by what they perceived as the North’s failure to understand and appreciate Southern culture. Thus, the principle goal of the Southwestern humorists was to defend and preserve the culture they loved, a culture which valued many of the subjects they wrote about (Cohen xv and xvii). Though Southwestern humor focuses on a wide range of subjects, including hunting, trading, violent practical jokes, fighting, and frolics (rural dances), the most common formula of Southwestern humor is the situation where an educated, white male travels to the Southern backwoods and attempts to practice his profession, generally law or medicine (Grammer 370). Southwestern humor then capitalizes on the tension resulting from the interactions between the upper class male and the coarse country characters by thrusting them together into humorous circumstances. Because the Southwestern humorists wished to create humor, it was necessary that the backwoods characters featured in their stories be caricatures. And from that requirement rose the distinguishing characteristic of Southwestern humor—its exaggerated presentation of rural Southern dialect. Southwestern humor thus introduced “linguistic deviance” to a wider American audience and paved the way for “a demotic deplored by all educators and lexicographers” to enter the vernacular (Justus 354 and 355). Although Southwestern humor utilizes many stereotypes for the white backwoods characters, African-American characters are generally confined to secondary roles, often appearing for a few pages and fading into the background afterward (Piacentino 116). The two most prevalent African-American stereotypes found in Southwestern humor are the loyal contented slave and the comic black (Piacentino 117). Adherence to these stereotypes is more or less absolute, but there are a few notable exceptions. The first exception is found in the work of John S. Robb whose story, “The Pre-Emption Right,” shows a black slave displaying compassion toward a white woman. This breaking of the African-American stereotype is radical because it presents a black slave acting on human impulses and showing human emotion (Piacentino 117). The second instance of a Southwestern humorist breaking the African-American stereotype is found in Hardin Taliaferro’s Fisher River. Taliaferro, in his novel, devotes two stories to the narrative voice of Reverend Charles Gentry, a black preacher. Taliaferro’s elevation of Reverend Gentry to the status of primary character is exceedingly rare within the realm of Southwestern humor (Piacentino 119). Francis James Robinson’s “Old Jack’ C—” is another story that features a black man as a primary character. In “Old Jack’ C—,” however, the black character is able to repeatedly manipulate white characters, showing that he is smarter than them and that he is superior to them (Piacentino 123). Obviously, the idea of a black character displaying superiority over white characters would not have been well-received in the pre-Civil War South. Perhaps for that reason, or perhaps because the humorists who challenged the African-American stereotypes did not realize they were doing so, the writers often buried under comedy and rendered unnoticeable the fact that they were defying the stereotypes. In this way, the humorists who dispute the stereotypes “often camouflaged or provided a buffer or safeguard for what they were doing” (Piacentino 117). Southwestern humor is vital to Southern literature because it marks the first time Southern writers attempted to represent the South to a wider audience outside the South. It represents the birth of Southern literature because elements of it would come to influence a wide breadth of Southern and American writers spanning several genres. Genres and writers influenced by Southwestern humor include the Southern gothic novels written by William Faulkner, the Grotesque stories of Flannery O’Connor, and the “grit lit” of Cormac McCarthy, Harry Crews, and Larry Brown. What’s more, Southwestern humor greatly influenced Mark Twain (MacKethan). In fact, the connection between Mark Twain and Southwestern humor has been examined in a number of books, such as Kenneth S. Lynn’s Mark Twain and Southwestern Humor and Pascal Covici’s Mark Twain’s Humor: The Image of a World. In devotion to the South, the humorists set out to preserve the culture they recognized as quickly falling away. In doing so, they often traded in stereotypes, but a few of them occasionally stepped outside of the cultural taboos to produce stories that violated those stereotypes. Though Southwestern Humor is of humble origin, it transcends that to become one of the most influential genres in American literature and the earliest distinctive form of Southern literature. Jaclyn Crumbley Sources

Further Information

To Tell a Free Story by William L. Andrews: In To Tell a Free Story, William L. Andrews analyzes how African-Americans first came to tell their own stories in the hundred years that preceded emancipation. Of main interest in his work is the interplay between black narrators and their white audience. He aims to define the moment in which black authors began to pen a truly free story, one that was unfettered by the social constructions of the day. He examines a broad range of black testimony, studying everything from the well-known texts of Frederick Douglass and Olaudah Equiano to a number of lesser known narratives. Andrews traces how black slaves transitioned from “defining the self according to traditional cultural models” into telling stories that focused on “those aspects of the self outside the margins of the normal, the acceptable, and the definable as conceived by predominant culture” (Andrews 2). By beginning to tell passionate, sophisticated “free stories,” Andrews argues, African-Americans took a giant leap toward self-liberation. During the first fifty years of slave narratives, from around 1760 to 1810, blacks sought the approbation of their white readers primarily through tales of acculturation and Christian conversion. The black narrator only “reported the basic ‘who-what-and-where’ of his past experience” to a white amanuensis-editor, who later crafted the narrative himself (Andrews 34). This process of filtering and trimming slave autobiography is what Andrews calls an act of “literary ventriloquism” (Andrews 35). During this time, most slave testimony only sought to patronize white readers with successful stories of a slave becoming cultured and benefiting from the “peculiar institution.” The narrative of New England slave Briton Hammon, penned in 1760, signaled the beginning of this period of literary accomodationism, to be followed later by similar narratives such as those of James Albert Ukawsaw Groniosaw in 1770 and John Marrant in 1785, as well as the anonymous narrative entitled A Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Venture a Native of Africa in 1798. In these narratives, slavery is usually never distinctly addressed. Only the personal enlightenment of the slaves at hand receives much attention. Starting around 1810, however, a number of abolitionist sponsors, such as the American Anti-Slavery Society, began to elicit help from slaves in publishing their stories as anti-slavery texts. These early abolitionists realized that the most effective means of combating slavery was to reach “the hearts of men” through the narratives of individual slaves (Andrews 5). But early abolitionist sponsors weren’t necessarily concerned with giving slaves an autonomous voice, Andrew argues. Rather, their primary goal was to promote the abolitionist cause. They knew that the public would “not read [slave] stories primarily to find out what kind of men these blacks were” but instead to “get a firsthand look at the institution of slavery” (Andrews 5). Naturally, many black narrators seemed inclined to give in to this expectation, especially given the fact that the skeptical white audience was likely only to believe objective, documentable facts in a slave narrative. Following that line of logic, abolitionist sponsors crafted slave narratives in a purely mimetic form, one “in which the self is on the periphery instead of at the center of attention, looking outside not within, transcribing rather than interpreting a set of objective facts” (Andrews 6). Slave narratives related only the bare facts about the horrors of slavery, but rarely allowed any rhetorical liberties. The problem with this form is that it prevented slaves from telling their own “free” story of personal experience, even if it did do so under the guise of promoting freedom. Slaves were still cast as an object of scientific curiosity––studied and presented by the pen of a white editor––rather than as idiosyncratic storytellers with literary and personal sovereignty. Not until the early 1840s does Andrews finally identify any real form of free storytelling coming from the pens of African-American writers. Ex-slaves skilled in the art of rhetoric such as Frederick Douglass, J.D. Green, and Harriet Jacobs began to comment more freely on their experiences in slavery and make sophisticated arguments opposing the institution. Granted, Andrews does concede this increase in literary freedom was partly because the 1840s represented a more receptive climate to a self-authorizing black voice than in the past, as it was the “first time in American literary history that both educational preparation and ideological justification for black autobiography existed on a scale sufficient” for the genre to survive (Andrews 99). Andrews does not discount black agency, however. He recognizes that by the 1840s, African-Americans had grown more willing to disregard the cultural forces prohibiting their free speech. In the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, “some of the first fruits of the emancipation of the black autobiographer under the influence of the cultural forces” comes to the forefront (Andrews 102). Douglass’s style, Andrews argues, does more than simply recite facts. It acts a signature of his individuality. As William Lloyd Garrison’s introduction to the narrative suggests, Douglass “very properly [chose] to write his own Narrative, in his own style . . . rather than to employ someone else” (Andrews 102). Andrews’s book encapsulates the first hundred years of African-American autobiography. In roughly a century, slaves went from telling “unfree stories” that they dictated to a white publisher, to producing sovereign literary works that expressed their selfhood. By developing a self-authorizing voice and relating their personal experiences to the public, African-Americans not only promoted the anti-slavery cause, but asserted themselves as “a man and brother to whites” (Andrews 1). That is, not only did black narrators argue for freedom, but through the very act of telling their stories, they freed themselves. Carl Lewis Further Information

|

r force, sugar merchants set their sights on African slaves as a source of cheap, sturdy, and expendable labor (Wagner).

r force, sugar merchants set their sights on African slaves as a source of cheap, sturdy, and expendable labor (Wagner).  John Brown was charged with treason, murder, and conspiracy, and he was assigned to a lawyer who sought to prove him insane. In an address to the court on November 2, 1859, Brown asserted that what he had done “was not wrong, but right.” Brown was the director and leading character of his apologetic drama, symbolically sacrificing himself for the antislavery cause (Burkholder 4-5). He was hanged a month later, meeting the same end as those who followed him in his failed attempt.

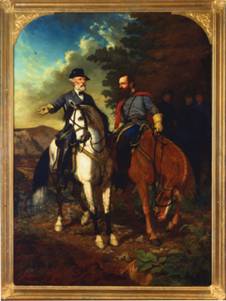

John Brown was charged with treason, murder, and conspiracy, and he was assigned to a lawyer who sought to prove him insane. In an address to the court on November 2, 1859, Brown asserted that what he had done “was not wrong, but right.” Brown was the director and leading character of his apologetic drama, symbolically sacrificing himself for the antislavery cause (Burkholder 4-5). He was hanged a month later, meeting the same end as those who followed him in his failed attempt.  As a result, Generals Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and Nathan Bedford Forrest were often the subjects of paintings and monuments. One example of such a painting is Everett B.D. Julio’s The Last Meeting, which portrays the conference between Generals Lee and Jackson before the Battle of Chancellorsville. The timing of the painting is especially poignant because Jackson later died due to wounds he received at Chancellorsville (Gallagher 149). The Last Meeting is also one of the most famous artistic symbols of the Lost Cause (Graves). In addition to lionizing Confederate military leaders, the Lost Cause represented the Confederate battle flag as a symbol of a tragic fight for independence, an effort which has been largely successful and has gained acceptance worldwide. In fact, the battle flag has cropped up repeatedly in Europe as signifying rebellion against tyranny, including at the Berlin Wall in 1988 where it was displayed in a sea of German flags (Coski 292-293 and Scroggins).

As a result, Generals Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and Nathan Bedford Forrest were often the subjects of paintings and monuments. One example of such a painting is Everett B.D. Julio’s The Last Meeting, which portrays the conference between Generals Lee and Jackson before the Battle of Chancellorsville. The timing of the painting is especially poignant because Jackson later died due to wounds he received at Chancellorsville (Gallagher 149). The Last Meeting is also one of the most famous artistic symbols of the Lost Cause (Graves). In addition to lionizing Confederate military leaders, the Lost Cause represented the Confederate battle flag as a symbol of a tragic fight for independence, an effort which has been largely successful and has gained acceptance worldwide. In fact, the battle flag has cropped up repeatedly in Europe as signifying rebellion against tyranny, including at the Berlin Wall in 1988 where it was displayed in a sea of German flags (Coski 292-293 and Scroggins).  literature at the end of the 19th century. Launched as an advertising icon in 1893, Aunt Jemima quickly became largely successful as her round, smiling face beamed out from pancake mix and syrup bottles. Aunt Jemima was widely supported and endorsed by whites, Northern and Southern, because her image tapped into the Lost Cause mythology of the “old Negro” and the “Old South.” Her image suggests a common, comforting historical memory that recalls a happy and familial southern living enjoyed by blacks and whites. As Wallace-Sanders points out, the recurring image of Mammy is so engrained in the American psyche that even the best white writers cannot escape her influence. While playing on the image, American authors Mark Twain and Charles Chesnutt inevitably tap into the mammy stereotype in unintentional ways.

literature at the end of the 19th century. Launched as an advertising icon in 1893, Aunt Jemima quickly became largely successful as her round, smiling face beamed out from pancake mix and syrup bottles. Aunt Jemima was widely supported and endorsed by whites, Northern and Southern, because her image tapped into the Lost Cause mythology of the “old Negro” and the “Old South.” Her image suggests a common, comforting historical memory that recalls a happy and familial southern living enjoyed by blacks and whites. As Wallace-Sanders points out, the recurring image of Mammy is so engrained in the American psyche that even the best white writers cannot escape her influence. While playing on the image, American authors Mark Twain and Charles Chesnutt inevitably tap into the mammy stereotype in unintentional ways.